“Hell,” says Mousaka. He raises a forefinger and circles it in the air, to indicate that he is referring to the whole of the void. I am sitting on Mousaka’s lap. Mousaka is sitting on Osiman’s lap. Osiman is sitting on someone else’s lap. And so on — everybody sitting on another’s lap. We are on a truck, crossing the void. The truck looks like a dump truck, though it doesn’t dump. It is 20 feet long and 6 feet wide, diesel powered, painted white. One hundred and ninety passengers are aboard, tossed atop one another like a pile of laundry. People are on the roof of the cab, and straddling the rail of the bed, and pressed into the bed itself. There is no room for carry-on bags; water jugs and other belongings must be tied to the truck’s rail and hung over the sides. Fistfights have broken out over half an inch of contested space. Beyond the truck, the void encompasses 154,440 square miles, at last count, and is virtually uninhabited.

Like many of the people on board, Mousaka makes his living by harvesting crops — oranges or potatoes or dates. His facial scars, patterned like whiskers, indicate that he is a member of the Hausa culture, from southern Niger. Mousaka has two wives and four children and no way to provide for them, except to get on a truck. Also on the truck are Tuareg and Songhai and Zerma and Fulani and Kanuri and Wodaabe. Everyone is headed to Libya, where the drought that has gripped much of North Africa has been less severe and there are still crops to pick. Libya has become the new promised land. Mousaka plans to stay through the harvest season, January to July, and then return to his family. To get to Libya from the south, though, one must first cross the void.

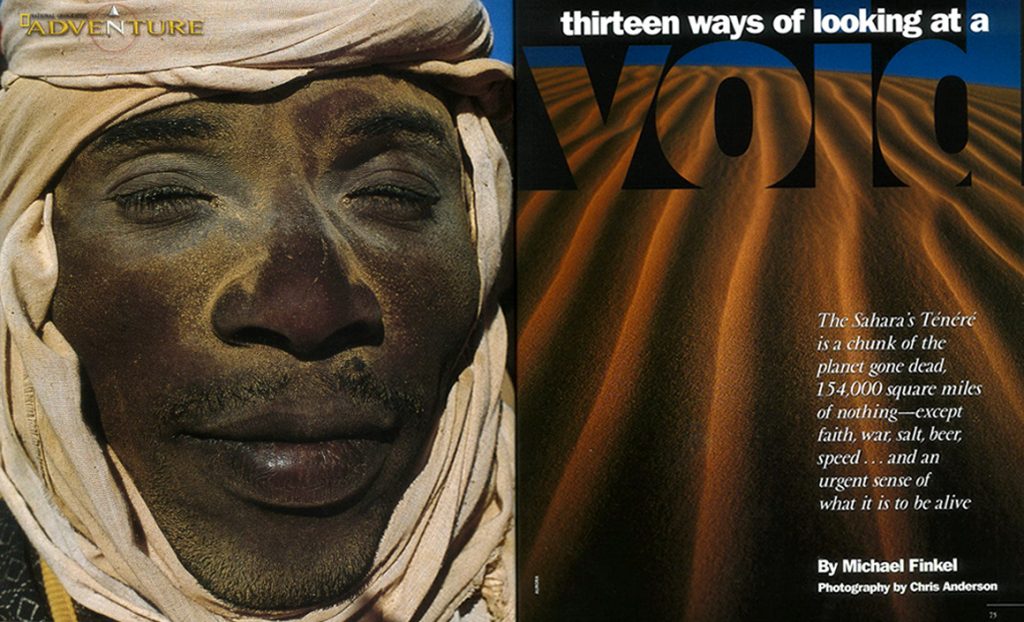

The void is the giant sand sea at the center of the Sahara. It covers half of Niger and some of Algeria and a little of Libya and a corner of Chad. On maps of the Sahara, it is labeled, in large, spaced letters, “Ténére” — a term taken from the Tuareg language that means “nothing” or “emptiness” or “void.” The Ténéré is Earth at its least hospitable, a chunk of the planet gone dead. Even the word itself, “Ténéré,” looks vaguely ominous, barbed as it is with accents. In the heart of the void there is not a scrap of shade nor a bead of water nor a blade of grass. Most parts, even bacteria can’t survive.

The void is freezing by night and scorching by day and wind-scoured always. Its center is as flat and featureless as the head of a drum. There is not so much as a large rock. Mousaka has been crossing the void for four days; he has at least a week to go. Except for praver breaks, the truck does not stop. Since entering the void, Mousaka has hardly slept, or eaten, or drunk. He has no shoes, no sunglasses, no blanket. His ears are plugged with sand. His clothing is tattered. His feet are swollen. This morning, I asked him what comes to mind when he thinks about the void. For two weeks now, as I’ve been crossing the Sahara myself, using all manner of transportation, I have asked this question to almost every person I’ve met. When the truck rides over a bump and everybody is jounced, elbows colliding with sternurns, heads hammering heads, Mousaka leans forward and tells me his answer again. “The desert is disgusting,” he says, in French. “The desert is hell.” Then he spits over the side of the truck, and spits again, trying to rid himself of the sand that has collected in his mouth.

—

“Faith,” says Monique. “The Ténéré gives me faith.” Monique has been crossing and recrossing the void for four weeks. We’ve met at the small market in the Algerian town of Djanet, at the northern hem of the Ténéré. Monique is here with her travel partners, resupplying. She’s Swiss, though she’s lived in the United States for a good part of her life. Her group is traversing the void in a convoy of Pinzgauers — six-wheel-drive, moon-rover-looking vehicles, made in Austria, that are apparently undaunted by even the softest of sands.

Monique is in her early 70s. A few years ago, not long after her husband passed away, she fulfilled a lifelong fantasy and visited the Sahara. The desert changed her. She witnessed sunrises that turned the sand the color of lipstick. She saw starfish-shaped dunes, miles across, whose curving forms left her breathless with wonder. She heard the fizzy hum known as the singing of the sands. She reveled he silence and the openness. She slept outside. She let the wind braid her hair and the sand sit under her fingernails and the sun bake skin. She shared meals with desert nomads. She learned that not every place on Earth is crowded and greed-filled and tamed. She stayed three months. Now she’s back for another extended visit.

Her story is not unusual. Tourism in the Ténéré is suddenly popular. Outfitters in Paris and London and Geneva and Berlin are chartering flights to the edge of the void and then arranging for vehicles that will take you to the middle. Look at the map, the brochures say: You’re going to the heart of the Sahara, to the famous Tenéré. Doesn’t the word itself, exotic with accents, roll off the tongue like a tiny poem?

Many of the tourists are on spiritual quests. They live hectic lives, and they want a nice dose of nothing — and there is nothing more nothing than the void. The void is so blank that a point-and-shoot camera will often refuse to work, the auto-focus finding nothing to focus on. This is good. By offering nothing, I’ve been told, the void tacitly accepts everything. Whatever you want to find seems to be there. Not long after I met Monique, I spoke with another American. Her name is Beth. She had been in the Ténéré for two and a half weeks, and she told me that the point of her trip was to feel the wind in her face. After a fortnight of wind, Beth came to a profound decision. She said she now realized what her life was missing. She said that the moment she returned home she was quitting her Internet job and opening up her own business. She said she was going to bake apple pies.

—

“Money,” says Ahmed. “Money, money, money, money, money.” Ahmed has no money. But he does have a plan. His plan is to meet every plane that lands in his hometown of Agadez, in central Niger, one of the hubs of Ténéré tourism. During the cooler months, and when the runway is not too potholed, a flight arrives in Agadez as often as once a week. When my plane landed, from Paris, Ahmed was there. The flight was packed with French vacationers, but all of them had planned their trips with European full-service agencies. No one needed to hire a freelance guide. This is why Ahmed is stuck talking with me.

Ahmed speaks French and English and German and Arabic and Hausa and Toubou, as well as his mother tongue, the Tuareg language called Tamashek. He’s 27 years old. He has typical Tuareg hair, jet black and wild with curls, and a habit of glancing every so often at his wrist, like a busy executive, which is a tic he must have picked up from tourists, for Ahmed does not own a watch, and, he tells me, he never has. He says he’s learned all these languages because he doesn’t want to get on a truck to Libya. He tells me he can help tourists rent quality Land Cruisers, and he can cook for them — his specialty is tagela, a bread that is baked in the sand — and he can guide them across the void without a worry of getting lost. Tourism, he says, is the only way to make money in the void.

Inside his shirt pocket, Ahmed keeps a brochure that was once attached to a bottle of shampoo. The brochure features photos of very pretty models, white women with perfect hair and polished teeth, and Ahmed has opened and closed the brochure so many times that it is as brittle and wrinkled as an old dollar bill. “When I have money,” says, “I will have women like this.”

“But,” I point out, “the plane landed, and you didn’t get a client.”

“Maybe next week,” he says.

“So how will you make money this week?”

“I just told you all about me,” he says. “Doesn’t that deserve a tip?”

—

“Salt,” says Choukou. He tips his chin to the south, toward a place called Bilma, in eastern Niger, where he’s going to gather salt. Choukou is on his camel. He’s sitting cross-legged, his head wrapped loosely in a long white cloth, his body shrouded in a billowy tan robe, and there is an air about him of exquisite levity — a mood he always seems to project when he is atop his camel. Often, he breaks into song, a warbling chant in the Toubou tongue, a language whose syllables are as rounded as river stones. I am riding another of his camels, a blue-eyed female that emits the sort of noises that make me think of calling a plumber. A half dozen other camels are following us, riderless. We are crossing the void.

Choukou is a Toubou, a member of one of the last seminomadic peoples to live along the edges of the void. At its periphery, the void is not particularly voidlike; it’s surrounded on three sides by craggy mountains — the Massif de l’Aïr, the Ahaggar, the Plateau du Djado, the Tibesti — and, to the south, the Lake Chad Basin. Choukou can ride his camel sitting frontward or backward or sidesaddle or standing, and he can command his camel, never raising his voice above a whisper, to squat down or rise up or spin in circles. His knife is strapped high on his right arm; his goatskin, filled with water, is hooked to his saddle; a few dried dates are in the breast pocket of his robe, along with a pouch of tobacco and some scraps of rolling paper. He is sitting on his blanket. This is all he has with him. It has been said that a Toubou can live for three days on a single date: the first day on its skin, the second on its fruit, the third on its pit. My guess is that this is truer than you might imagine. In two days of difficult travel with Choukou, I saw him eat one meal.

If you ask Choukou how old he is, he’ll say he doesn’t know. He’s willing to guess (20, he sup-

poses), but he can’t say for sure. It doesn’t matter. His sense of time is not divided into years or seasons or months. It’s divided into directions. Either he is headed to Bilma, to gather salt, or he is headed away from Bilma, to sell his salt. It has been this way for the Toubou for 2,000 years. No one has yet discovered a more economical method of transporting salt across the void — engines and sand are an unhappy mix — and so camels are still in use. Camels can survive two weeks between water stops and then, in a single prolonged drink, can down 25 gallons of water, none of which happens to be stored in the hump. When Choukou arrives at the salt mines of Bilma, he will load each of his camels with six 50-pound pillars of salt, then join with other Toubou to form a caravan — a hundred or more camels striding single file across the sands — and set out for Agadez. In the best of conditions, the trek can take nearly a month.

Choukou occasionally encounters tourists, and he sometimes sees the overloaded trucks, but he is only mildly curious. He does not have to seek solace from a hectic life. He has no need to pick crops in Libya. He travels with the minimum he requires to survive, and he knows that if even one well along the route has suddenly run dry — it happens — then he will probably die. He knows that there are bandits in the void and sandstorms in the void. He is not married. A good wife, he tells me, costs five camels, and he can’t yet afford one. If he makes it to Agadez, he will sell his salt and then immediately start back to Bilma. He navigates by the dunes and the colors of the soil and the direction of the wind. He can study a set of camel tracks and determine which breed of camel left them, and therefore the tribe to which they belong, and how many days old the tracks are, and how heavy a load the camels are carrying, and how many animals are in the caravan. He was born in the void, and he has never left the void. This is perhaps why he looks at me oddly when I ask him what comes to mind when he contemplates his homeland. I ask him the question, and his face becomes passive. He mentions salt, but then he is quiet for a few seconds. “I really don’t think about the void,” he says.

—

“Cameras,” says Mustafa. “Also videos and watches and Walkmans and jewelry and GPS units.” Mustafa has an M16 rifle slung over his shoulder. He is trying to sell me the items he has taken from other tourists. I am at a police checkpoint in the tiny outpost of Chirfa, along the northeastern border of the void. I’ve hired a desert taxi — a daredevil driver and a beater Land Cruiser — to take me to Algeria. Now we’ve been stopped.

Mustafa is fat. He is fat, and he is wearing a police uniform. This is a bad combination. In the void, only the wealthy are fat. Police in Niger do not make enough money to become wealthy; a fat police officer is therefore a corrupt police officer. And a corrupt officer inevitably means trouble. When I refuse to even look at his wares, Mustafa becomes angry. He asks to see my travel documents. The void is a fascinating place — there exist, at once, both no rules and strict rules. To cross the void legally, you are supposed to carry very specific travel documents, and I actually have them. But the documents are open to interpretation. You must, for example, list your exact route of travel. It is difficult to do this when you are crossing an expanse of sand that has no real roads. So of course Mustafa finds a mistake.

“It is easy to correct,” he says. “You just have to return to Agadez.” Agadez is a four-day drive in the opposite direction. “Or I can correct it here,” he adds. “Just give me your GPS unit.” He does not even bother to pretend that it isn’t a bribe. Mustafa is the leader of this outpost, the dictator of a thousand square miles of desert. There is no one to appeal to.

“I don’t have a GPS unit,” I say.

“Then your watch.”

“No,” I say.

“A payment will do.”

“No,” I say.

“Fine,” he says. Then he says nothing. He folds his arms and rests them on the shelf formed by his belly. He stands there for a long time. The driver turns off the car. We wait. Mustafa has all day, all week, all month, all year. He has no schedule. He has no meetings. If we try to drive away, he will shoot us. It is a losing battle.

I hand him a sheaf of Central African francs, and we continue on.

—

“Beer,” says Grace. “Beer and women.” Grace is maybe 35 years old and wears a dress brilliant with yellow sunflowers. She has a theory: Crossing the void, she insists, seeing all that nothing, she posits, produces within a man a certain kind of emptiness. It is her divine duty, she’s decided, to fill that emptiness. And so Grace has opened a bar in Dirkou. A bar and brothel.

Dirkou is an unusual town. It’s in Niger, at the northeastern rim of the Ténéré, built in what is known as a wadi — an ancient riverbed, now dry, but where water exists not too far below the surface, reachable by digging wells. The underground water allows date palms to grow in Dirkou. Whether you are traveling by truck, camel, or 4×4, it is nearly impossible to cross the void without stopping in Dirkou for fuel or provisions or water or emptiness-filling.

Apparently, it is popular to inform newcomers to Dirkou that they are now as close as they can get to the end of the Earth. My first hour in town, I was told this five or six times; it must be a sort of civic slogan. This proves only that a visit to the end of the Earth should not be on one’s to-do list. Dirkou is possibly the most unredeeming place I have ever visited, Los Angeles included. The town is essentially one large bus station, except that it lacks electricity, plumbing, television, newspapers, and telephones. Locals say that it has not rained here in more than two vears. The streets are heavy with beggars and con artists and thieves and migrants and drifters and soldiers and prostitutes. Almost evervone is male, except the prostitutes. The place is literally a dump: When you want to throw something away, you just toss it in the street.

Grace’s emptiness theory has a certain truth. I arrived in Dirkou after riding on the Libya-bound truck for three days. Of the 190 passengers, 186 were male. Those with a bit of money went straight to Grace’s bar. The bar was like every structure in Dirkou: mud walls, palm-frond roof, sand floors. I sat at a scrap-wood table, on a milk-crate chair. A battery-powered radio emitted 90 percent static and 10 percent Arabic music from a station in Chad. I drank a Niger beer, which had been stored in the shade and was, by Saharan standards, cold. I drank two more.

My emptiness, it seems, was not as profound as those of my truck mates. In the Ténéré, there exists the odd but pervasive belief that alcohol hydrates you — and not only hydrates you but hydrates you more efficiently than water. Some people on the truck did not drink at all the last day of the trip, for they knew Grace’s bar was approaching. Many of these same men were soon passed out in the back of the bar. There is also the belief that a man cannot catch AIDS from a prostitute so long as she is less than 18 years old.

One other item that Dirkou lacks is bathrooms. After eating a bit of camel sausage and drinking my fourth beer, I ask Grace where the bathroom is. She tells me it is in the street. I explain, delicately, that I’m hoping to produce a different sort of waste. She says it doesn’t matter, the bathroom is in the street. I walk out of the bar, seeking a private spot, and in the process I witness three men doing what I am planning to do. This explains much about the unfortunate odor that permeates Dirkou.

—

“Spirits,” says Wordigou. He is siting on a blanket and holding his supper bowl, which at one time was a sardine tin. His face is illuminated by a kerosene lamp. Wordigou has joined us for dinner, some rice and a bit of mutton. He is a cousin of Choukou’s, the young salt trader who told me that he does not think about the void. Choukou allowed me to join his camel trek for two days, and now, in the middle of our journey, we have stopped for the evening at a Toubou encampment. Wordigou lives in the camp, which consists of a handful of dome-shaped grass huts, two dozen camels, an extended family of Toubou, and a herd of goats. In the hut I’ve been lent for the night, a cassette tape is displayed on the wall as a sort of curious knickknack. Certainly there is no tape player in the camp. Here, the chief form of entertainment is the same as it is almost everywhere in the void — talking. Wordigou, who guesses that he is a little less than 30 years old, leads the mealtime discussion. He is a sharp and insightful conversationalist. The topic is religion. The Toubou are nominally Muslim, but most, including Wordigou, have combined Islam with traditional animist beliefs.

“The desert,” says Wordigou, “is filled with spirits. I talk with them all the time. They tell me things. They tell me news. Some spirits you see, and some you don’t see, and some are nice, and some are not nice, and some pretend to be nice but really aren’t. I ask the nice ones to send me strong camels. And also to lead me to hidden treasures.”

Wordigou catches my eye, and he knows immediately that I do not share his beliefs. Still, he is magnanimous. “Even if you do not see my spirits,” he says, “you must see someone’s. Everyone does. How else could Christianity and Judaism and Islam all have begun in the very same desert?”

—

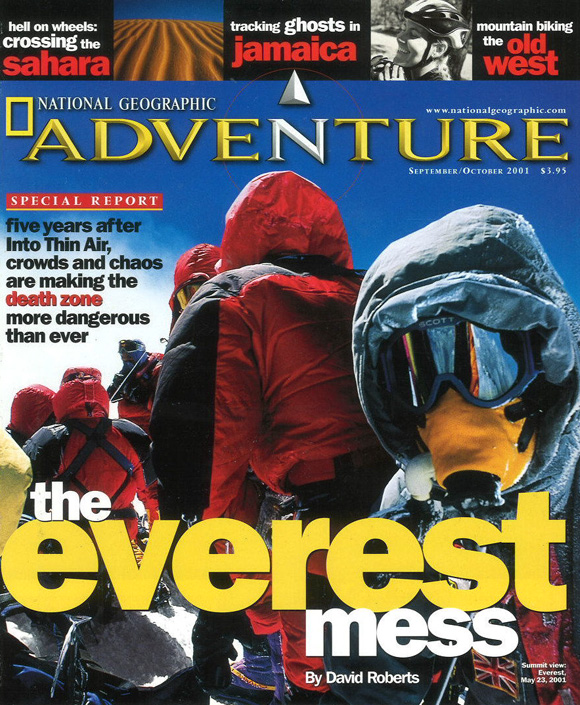

“Work,” says Bilit. “It ties me to the desert.” Bilit is the driver of the overloaded truck that is headed to Libya. He has stopped his vehicle, climbed out of the front seat, and genuflected in the direction of Mecca. Sand is stuck to his forehead. The passengers who’ve gotten off are piling aboard. Only their turbans can be seen through the swirling sand. Everyone wears a turban in the void – it protects against sun and wind and provides the wearer with a degree of anonymity, which can be valuable if one is attempting a dubiously legal maneuver, like sneaking into Libya. Turbans are about the only splashes of color in the desert. They come in a handful of bold, basic hues, like gum ball. Bilit’s is green. I ask him how far we have to go.

“Two days,” says Bilit. “Inshallah,” he adds — God willing. He says it again: “Inshallah.” This is, by far, the void’s most utilized expression, the oral equivalent of punctuation. God willing. It emphasizes the daunting fact that, no matter the degree of one’s preparation, traveling the void always involves relinquishing control. Bilit has driven this route — Agadez to Dirkou, 400 miles of void — for eight years. When conditions allow, he drives 20 to 22 hours a day. Where the sand is firm, Bilit can drive as fast as 15 miles an hour. Where it is soft, the passengers have to get out and push. Everywhere, the engine sounds as though it is continually trying to clear its throat.

His route is one of the busiest in the Ténéré — sometimes he sees three or even four other vehicles a day. This means that Bilit doesn’t need to rely on compass bearings or star readings to determine if he is headed in the correct direction. There are actually other tire tracks in the sand to follow. Not all tracks, however, are reliable. A “road” in the Ténéré can be 20 miles wide, with tracks braiding about one another where the drivers detoured around signs of softness, seeking firmer sand. Inexperienced drivers have followed braided tracks and ended up confounding themselves. In a place with a blank horizon, it is impossible to tell if you’re headed in a gradual arc or going straight. Drivers have followed bad braids until they’ve run out of gas.

Worse is when there are no tracks at all. This happens after every major sandstorm, when the swirling sands return the void to blankness, shaken clean like an Etch A Sketch. A sandstorm occurs, on average, about once a week. During a storm, Bilit stops the truck. Sometimes he’ll be stopped for two days. Sometimes three. The passengers, of course, must suffer through it; they are too crowded to move. The trucks are so crowded because the more people aboard, the more money the truck’s owner makes. The void is a place where crude economics rule. Comfort is rarely a consideration.

One time, Bilit did not stop in a sandstorm. He got lost. Getting lost in the void is a frightening situation. Even with a compass and the stars, you can easily be off by half a degree and bypass an entire town. Bilit managed to find his way. But recently, on the same route, a truck was severely lost. There are few rescue services in the Ténéré, and by the time an army vehicle located the truck, only eight people were alive. Thirty-six corpses were discovered, all victims of dehydration. The rest of the passengers — six at least, and possibly many more — were likely buried beneath the sands and have never been found.

—

“War,” says Tombu. Where I see dunes, Tombu sees bunkers. Tombu is a soldier, a former leader of the Tuareg during the armed rebellion that erupted in Niger in 1990. Warring is in his blood. For more than 3,000 years, until the French overran North Africa in the late 1800s, the Tuareg were known as the bandits of the Ténéré, robbing camel caravans as they headed across the void.

The fighting that began in 1990, however, was over civil rights. Many Tuareg felt like second-class citizens in Niger — it was the majority Hausa and other ethnic groups, they claimed, who were given all the good jobs, the government positions, the college scholarships. And so these Tuareg decided to try to gain autonomy over their homeland, which is essentially the whole of the Ténéré. They were fighting for an Independent Republic of the Void. Hundreds of people were killed before a compromise was reached in 1995: The Tuareg would be treated with greater respect, and in return they would agree to drop their fight for independence. Though isolated skirmishes continued until 1998, the void is quiet, at least for now. This is a main reason why there has been a sudden upswing in tourism.

Tombu is no longer a fighter; he now drives a desert taxi, though he drives like a soldier, which is to say as recklessly as possible. I have hired him to take me north, through the center of the void, into Algeria — a four-day drive. We were together when the police officer forced me to pay him a bribe. During rest stops, Tombu draws diagrams in the sand, showing me how he attacked a post high in the Massif de l’Aïr and how he ambushed a convoy of jeeps in the open void. “But now there is peace,” he says. He looks disappointed. I ask him if anything has changed for the Tuareg.

“No,” he says. “Except that we have given up our guns.” He looks even more disappointed. “But,” he adds, visibly brightening, “it will be very easy to get them back.”

—

“Speed,” says Joel. He has just pulled his motorbike up to the place I’ve rented in Dirkou, a furnitureless, sand-floored room for a dollar a night. Joel is in the desert for one primary reason: to go fast. He is here for two months, from Israel, to ride his motorbike, a red-and-white Yamaha, and the void is his playground. Speed and the void have a storied relationship; each winter for 13 years, the famous Paris-to-Dakar rally cut through the Ténéré — a few hundred foreigners in roadsters and pickup trucks and motorbikes tearing hell-bent across the sand. The race was rerouted in 1997, but its wrecks are still on display, each one visible from miles away, the vehicles’ paint scoured by the wind-blown sand and the steel baked to a smooth chocolate brown.

Joel reveres the Paris-to-Dakar. He talks about sand the way skiers talk about snow — in a language unintelligible to outsiders. Sand, it turns out, is not merely sand. There are chotts and regs and oueds and ergs and barchans and feche-feche and gassis and bull dust. The sand around Dirkou, Joel tells me, is just about perfect. “Would you like to borrow my bike?” he asks.

I would. I snap on his helmet and straddle the seat and set out across the sand. The world before me is an absolute plane, nothing at all, and I throttle the bike and soon I’m in fifth and the engine is screaming and sand is tornadoing about. I know, on some level, that I’m going fast and that it’s dangerous, but the feeling is absent of fear. The dimensions are so skewed it’s more like skydiving – I’ve committed myself, and now I’m hurtling through space, and there is nothing that can hurt me. It’s euphoric, a pure sense of motion and G-force and lawlessness, and I want more, of course, so I pull on the throttle and the world is a blur and the horizon is empty, and it is here, it is right now, that I suddenly realize what I need to do. And I do it. I shut my eyes. I pinch them shut, and the bike bullets on, and I override my panic because I know that there’s nothing to hit, not a thing in my way, and soon, with my eyes closed, I find that my head has gone silent and I have discovered a crystalline form of freedom.

—

“Death,” says Kevin. “I think abour dying.” Kevin is not alone. Everyone who crosses the void, whether tourist or Toubou or truck passenger, is witness to the Ténéré’s ruthlessness. There are the bones, for example — so many bones that a good way to navigate the void is to follow the skeletons, which are scattered beside every main route like cairns on a hiking trail. They’re mostly goat bones. Goats are common freight in the Ténéré, and there are always a couple of animals that do not survive the crossing. Dead goats are tossed off the trucks. In the center of the void, the carcasses become sun-dried and leathery, like mummies. At the edges of the void, where jackals roam, the bones are picked clean and sun-bleached white as alabaster. Some of the skeletons are of camels; a couple are human. People die every year in the Ténéré, but few travelers have experienced such deaths as directly as Kevin.

Kevin is also on the Libya-bound truck, crossing with the crop pickers, though he is different from most other passengers. He has no interest in picking crops. He wants to play soccer. He’s a midfielder, seeking a spot with a professional team in either Libya or Tunisia. Kevin was born in South Africa, under apartheid, then later fled to Senegal, where he lived in a refugee camp. His voice is warm and calm, and his eyes, peering through a pair of metal-framed glasses, register the sort of deep-seated thoughtfulness one might look for in a physician or religious leader. Whenever a fight breaks out on the truck, he assumes the role of mediator, gently persuading both parties to compromise on the level of uncomfortableness. He tells me that he would like to study philosophy and that he has been inspired by the writings of Thomas Jefferson. He says that his favorite musician is Phil Collins. “When I listen to his music,” he says, “it makes me cry.” I tell him, deadpan, that it makes me cry, too. This is Kevin’s second attempt at reaching the soccer fields across the sands. The first trip, a year previous, ended in disaster.

He was riding with his friend Silman in a dilapidated Land Cruiser in the northern part of the void. Both of them dreamed of playing soccer. There were six other passengers in the car and a driver, and for safety they were following another Land Cruiser, creating a shortcut across the Ténéré. The car Kevin and Silman were in broke down. There was no room in the second Land Cruiser, so only the driver of the first car squeezed in. He told his passengers to wait. He said he’d go to the nearest town, a day’s drive away, and then return with another car.

After three days, there was still no sign of the driver. Water was running low. It was the middle of summer. Temperatures in the void often reach 115 degrees Fahrenheit and have gone as high as 130 degrees. The sky turns white with heat; the sand shimmers and appears molten. Kevin and Silman decided they would rather walk than wait. The other six passengers decided to remain with the broken vehicle. Kevin and Silman set out across the desert, following the tracks of the second Land Cruiser. Merely sitting in the shade in the Sahara, a person can produce two gallons of sweat per day. Walking, Kevin and Silman probably produced twice that amount. They carried what water they had, but there was no way they could replace a quarter of the loss.

Humans are adaptable creatures, but finely calibrated. Even a gallon loss — about 5 percent of one’s body fluid — results in dizziness and headache and circulatory problems. Saliva glands dry up. Speech is garbled. Kevin and Silman reached this state in less than a day. At a two-gallon deficit, walking is nearly impossible. The tongue swells, vision and hearing are diminished, and one’s urine is the color of dark rust. It is difficult to form cogent thoughts. Recovery is not possible without medical assistance. People who approach this state often take desperate measures. Urine is the first thing to be drunk. Kevin and Silman did this. “You would’ve done it, too,” Kevin tells me. People who have waited by stranded cars have drunk gasoline and radiator fluid and battery acid. There have been instances in which people dying of thirst have killed others and drunk their blood.

Kevin and Silman managed to walk for three days. Then Silman collapsed. Kevin pushed on alone, crawling at times. The next day, the driver returned. He came upon Kevin, who at this point was scarcely conscious. The driver had no explanation for his weeklong delay. He gave Kevin water, and they rushed to find Silman. It was too late. Silman was dead. They returned to the broken Land Cruiser. Nobody was there. Evidently, the other passengers had also tried to walk. Their footprints had been covered by blowing sand. After hours of searching, there was no trace of anyone else. Kevin was the only survivor.

—

“History,” says Hamoud. Hamoud is an old man — though “old” is a relative term in Niger, where the life expectancy is 41. I have hired a desert taxi to take me to a place called Djado, in eastern Niger, where Hamoud works as a guide. Diado is, by far, the nicest city I have seen in the Ténéré. It is built on a small hill beside an oasis thick with date palms and looks a bit like a wattle-and-daub version of Mont Saint-Michel. The homes, unlike any others I’ve seen in the void, are multistoried, spacious, and cool. Thought has been given to the architecture; walls are elliptical, and turrets have been built to provide views of the surrounding desert. There is not a scrap of garbage.

One problem: Nobody lives in Djado. The city is several thousand years old and has been abandoned for more than two centuries. At one time, there may have been a half million people living along Djado’s oasis. Now it is part of a national reserve and off-limits to development.

A handful of families are clustered in mud shanties a couple of miles away, hoping to earn a few dollars from the trickle of tourists.

Nobody knows exactly why Djado was deserted; the final blows were most likely a malaria epidemic and the changing patterns of trade routes. But Hamoud suggests that the city’s decline was initiated by a dramatic shift in the climate. Ten thousand years ago, the Sahara was green. Giraffes and elephants and hippos roamed the land. Crocodiles lived in the rivers. On cliffs not far from Djado, ancient paintings depict an elaborate society of cattle herders and fishermen and bow hunters. Around 4000 b.c., the weather began to change. The game animals left. The rivers dried. One of the last completed cliff paintings is of a cow that appears to be weeping, perhaps symbolic of the prevailing mood. When Djado was at its prime, its oasis may have covered dozens of square miles. Now there is little more than a stagnant pond. Hamoud says that he found walking through Djado to be “mesmerizing” and “thrilling” and “magnificent” and “beautiful.” I do not tell him this, but my overwhelming feeling is of sadness. In the void, it seems clear, people’s lives were better a millennium ago than they are today.

—

“Destiny,” says Akly. He shrugs his shoulders in a way designed to imply that he could care less, but his words have already belied his gesture. Akly does care, but he is powerless to do anything — and maybe this, in truth, is what his shrug is attempting to express. Akly is a Tuareg, a native of Agadez who was educated in Paris. He has returned to Niger, with his French wife, to run a small guest house. Agadez is a poor city in a poor nation beset by a brutal desert. It is not a place to foster optimism.

Akly is worried about the Sahara. He is concerned about its expansion. Most scientific evidence appears to show that the Sahara is on the march. In three decades, the desert has advanced more than 60 miles to the south, devouring grasslands and crops, drying up wells, creating refugees. The Sahara is expanding north, too, piling up at the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, as if preparing to ambush the Mediterranean.

Desertification is a force as powerful as plate tectonics. If the Sahara wants to grow, it will grow. Akly says he has witnessed, just in his lifetime, profound changes. He believes that the desert’s growth is due both to the Sahara’s own forces and to human influences. “We cut down all the trees,” he says, “and put a hole in the ozone. The Earth is warming. There are too many people. But what can we do? Everyone needs to eat, everyone wants a family.” He shrugs again, that same shrug.

“It has gotten harder and harder to live here,” he says. “I am glad that you are here to see how hard it is. I hope you can get accustomed to it.”

I shake my head no and point to the sweat beading my face, and to the heat rash that has pimpled my neck, and to the blotches of sunburn that have left dead skin flaking off my nose and cheeks and arms.

“I think you’d better get used to it,” Akly says. “I think everyone should get used to it. Because one day, maybe not that far away, all of the deserts are going to grow. They are going to grow like the Sahara is growing. And then everyone is going to live in the void.”

— end —