A little before noon on the last day of his life, fifteen-year-old Ahmed Abutayeh invented a toothache. This was the first time he had ever complained of a health problem in school, so his science teacher wrote him a permission slip to visit a nearby clinic. Ahmed shouldered his plaid-patterned book bag and walked out of the Rimal Boys’ School and onto the chaotic streets of Beach Camp, where 75,000 Palestinian refugees were corralled into a half-square-mile block, at the northern end of the Gaza Strip. It was November 1, 2000. The previous day, Ahmed had sold his pet nightingale for a few shekels, and now, carrying this money, he caught a taxi and asked to be driven to a place called Karni Crossing. He was wearing the nicest shirt he owned, a light blue button-down, and a few dabs of his father’s cologne. On the outside of his book bag, in blue ink, he had inscribed a four-word epitaph: “The Martyr Ahmed Abutayeh.”

Karni Crossing, as its name implies, is an intersection. It’s where the Karni Road crosses the so-called Green Line, the razor-wire border dividing Gaza from Israel. The Gaza Strip is a place small enough to be easily fenced. It pokes from the northern end of the Egypt-Israel border and follows the shoreline of the Mediterranean Sea; its silhouette is roughly that of a pistol, aimed just west of Jerusalem. Karni Crossing is at a point about midway along the pistol’s barrel.

Palestinians were not allowed through the Karni Crossing. The road was reserved for Israeli access to a settlement called Netzarim. Forty percent of the Gaza Strip’s land, in 2000, was controlled by Israel and was home to 6,500 or so Israeli settlers, many of whom believed they had a property claim spelled out in the Old Testament. The other sixty percent was home to more than a million Palestinians, half of whom lived in refugee camps. Most Israeli settlements in Gaza were clustered in one of the large, fortified areas at both ends of the strip, but Netzarim was in the middle, an Israeli island in a Palestinian sea. There was something about the Karni Crossing, several Palestinians told me, that seemed emblematic of the entire half-century-long Israeli-Palestinian conflict: It was a place where Arabs were not considered equal citizens, in an area dominated by the Israeli armed forces, permitting entrance to a settlement provocatively situated to deny the Palestinians a homeland. So when there was fighting, it made sense that Karni Crossing was a scene of daily clashes. This is why Ahmed Abutayeh wanted to go there.

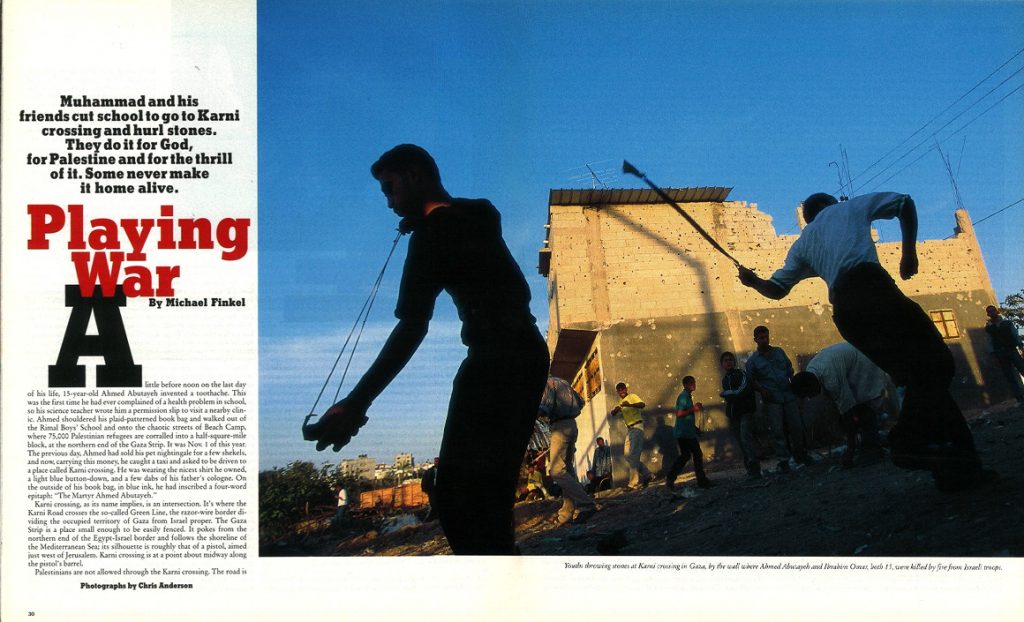

The confrontation on the day Ahmed took the taxi was intense. The Israeli Defense Forces had placed a tank and two armored vehicles along the Karni Road, trying as usual to maintain a safe route for settlers to pass through. Also beside the road, crouched in dirt trenches and behind cement barricades, were at least a hundred Palestinians, all of them male and many of them, like Ahmed, too young to be away from school. The boys Ahmed’s age were armed with stones and Molotov cocktails. A few older fighters, wearing dark green uniforms indicating membership in the loosely controlled Palestinian security services, carried guns.

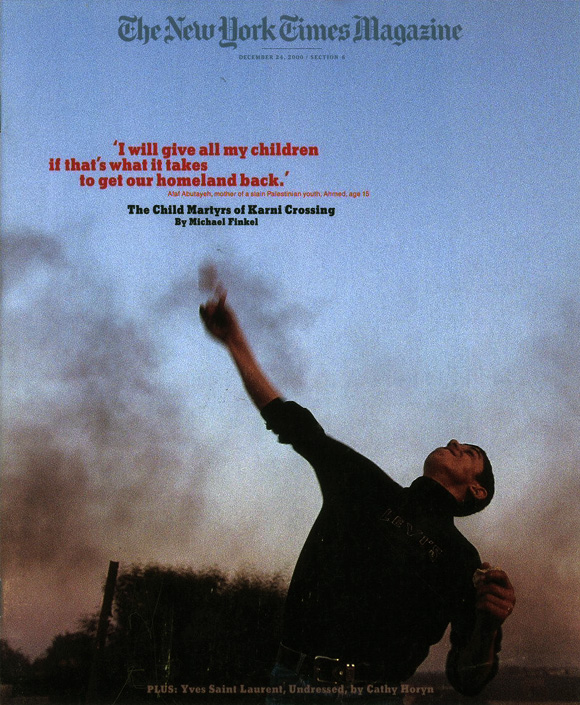

Ahmed had a sling with him, made of a bit of denim the size of an eye patch and a long piece of twine. He’d cup a stone in the denim, twirl the sling about his head, then snap the line taut. By all accounts he was a fierce and fearless stone-slinger. Sometime around four o’clock, as the desert sun was low and the dust that hovers about the Gaza Strip turned golden, the level of violence escalated. Two carloads of settlers wanted to drive through, and the Palestinians showed no signs of permitting a trouble-free passage. Live ammunition was fired from the Israeli side. Many of the boys fled or dove behind barricades, but Ahmed continued to twirl his sling. He did not seem concerned about finding protection. He stood up and flung another stone. A bullet from an M-16 struck Ahmed just above his right ear. The bullet was traveling at a downward angle, and it passed through his head and throat and settled in his chest. He was dead before an ambulance crew could reach him. The permission slip from his science teacher was found in the front pocket of his blue jeans.

—

This is a strange war. The rhetoric and geo-politics of the conflict — the claims of Biblical or Koranic privilege; the push-pull of Middle Eastern power; the status of refugee rights and occupied lands and religious sovereignty — are all cast in the loftiest of ideals. And yet, on the Palestinian side at least, much of the fighting is being carried out by children. There are preteenagers and midteenagers and boys as young as five hurling stones at Israeli soldiers. Children are dying with shocking frequency. In the three months before I traveled to Gaza, at least sixty-eight boys under the age of eighteen were killed and thousands wounded in clashes in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. The violence, though, does not deter the children; quite the opposite, in fact.

The day after Ahmed’s death, there were more boys at Karni Crossing than ever before. At the front, in the trenches, the energy level felt wild and unfocused and adolescent; not much different, really, than an unruly middle-school recess. Here I met half a dozen boys who’d known Ahmed: I met Muhammad and Sameh and Hares and Yehya and Aymen and Rami. All of them were thirteen or fourteen or fifteen years old, skinny and dirty and friendly. Each held a couple of rocks in his hands and jiggled them idly. Protruding from back pockets, where one might expect to see combs, were wooden slingshots and denim-and-twine slings.

Aymen wore silver-framed glasses that sat crooked on his nose and sported a strip of cloth tied ninja-style about his head, upon which he’d written, “Better to die a martyr than die in your sleep.” Rami’s left wrist was bandaged; he’d been hit, he said, by a rubber bullet. I commented on his bravery, and all the boys lifted their shirts or raised their pants legs to show me various scars. Each one said they’d seen people die. Hares insisted that the red stain on his shirt was Ahmed’s blood; he’d tried to stem the bleeding until the medics arrived, he said, but the attempt was hopeless.

Hares was one of the unofficial leaders of the front. He seemed perpetually agitated, in the noisy, inexhaustible manner of a child who might benefit from Ritalin. During a stone-throwing volley, he’d always leap up first, or nearly so, and he leapt in a way that seemed designed for maximum bravado, leaving himself exposed as if daring the soldiers to fire at him. Most of the boys appeared to admire this, but Muhammad admitted to me that he sometimes worries about Hares.

Muhammad was a little calmer than the others and more cautious, and only slightly averse to introspection. He had gone to school with Ahmed — they were in the same class — and Muhammad’s family lived a few doors down from Ahmed’s, in the center of Beach Camp. They’d been friends, Muhammad said. Muhammad had an easy, inviting grin, a slight fuzz of a mustache and front teeth just shy of being buck. He kept a stash of roasted watermelon seeds in his pocket and nibbled them in the smooth, casual way a smoker handles his cigarettes. The trenches weren’t the place for lengthy conversation, but Muhammad mentioned that if I met him after school tomorrow we could talk. I told him I would.

The fighting progressed in fits and starts. Sameh owned a pair of binoculars, and though one eyepiece was broken they were still usable. He focused on an Israeli tank, one hundred feet away, and studied the soldier in the hatch, helmet lowered to his eyebrows, straps tight against his cheeks, his mouth a thin pair of lines, one hand about the trigger of his rifle and an eye at the scope, watching the boys watching him. The vehicle crept along the Green Line, and when it reached the spot directly in front of us there was a surge of momentum, twenty or thirty boys leaping up at once, the air a hailstorm of stones. The soldier ducked into the hatch and the stones fell harmlessly against the tank. There was no return fire, but the boys all said it was only a matter of time before the Israelis’ patience wore thin.

—

The exceptionally large turnout at Karni didn’t happen by chance. Dozens of fighters were there specifically because of Ahmed. Most had not known him personally, but his martyrdom had been embraced by the Palestinian leadership and transformed, in short order, into a powerful recruiting device. Within an hour of Ahmed’s shooting, his mother, Afaf, was perched on the edge of a bed in Shifa Hospital, where her son had been pronounced dead. She was wrapped in a black headdress and robe, her eyes furious and red as she looked into a Palestinian Broadcasting Corporation television camera. She spoke in Arabic, using the baroque argot of the uprising, rhythmic and sharp. “Who killed my son, who shot my son, I am asking God to kill him, to spread his blood,” she intoned. “We must flood Israel with blood like they have flooded us with blood. Let their blood wash them out of Palestine.”

Two other Palestinians were also killed in Gaza the same day. One of them, Ibrahim Omar, was a friend and classmate of Ahmed’s. Ibrahim, too, was fifteen years old. He was shot in the neck while standing behind the same barricade where Ahmed had earlier been killed. The third victim was a seventeen-year-old named Muhammad Hajjaj. Ibrahim and Muhammad’s families also delivered pleas for vengeance. These were broadcast throughout Gaza, on radio and television, along with an announcement that the three funerals would be conducted simultaneously the following day. Schools would be released early, it was reported, so that students could attend.

The next morning, in the minutes before Ahmed and Ibrahim and Muhammad’s funeral procession was scheduled to arrive, Gaza City was quiet. All of the buildings — five, six, seven stories tall — appeared to be constructed of cinder blocks. There were cracks in some walls wide enough to offer glimpses of the apartments inside. Falafels were frying at outdoor stands; groceries sold cigarettes and soft drinks and penny candies. Tea shops were open. Clattering over the broken pavement came a mule-drawn cart, transporting a crateload of live chickens, dirty and squawkless. A few taxis passed. A bright new banner was stretched across the road, and my translator read it aloud: “Glory and Eternity for Our Martyrs.”

Faces of the dead gazed from dozens of posters. Within hours of the boys’ shootings, printing presses across Gaza had begun churning out posters. Each featured a head shot of one of the dead teenagers superimposed in front of the giant, gilded Dome of the Rock, in Jerusalem’s Old City, the place where the Prophet Muhammad is thought to have ascended to heaven. In the posters’ upper right-hand corner was an outline of the State of Israel, shaded in the colors of the Palestinian flag.

From down the street came the sound of chanting, and there seemed to be a change in the air, a ratcheting of pressure, as if a storm front were approaching. The demonstration blew in. At its head were three pickup trucks, each ferrying a stack of concert-size loudspeakers. An announcer stood atop each stack, shouting into a microphone, his voice so amplified and reverberative that the words felt as if they were being hurled outward, smacking against our ears and chest.

The trucks crept forward, each enmeshed by a turbulent crowd, shouting and reacting to the announcer’s calls, many of the marchers spreading their fingers into victory signs. A man held up a Kalashnikov and fired round after round into the simmering sky. “Will we forgive those who killed our children?” cried one truck’s preacher, his face a commingling of rapture and grief.

“No!” responded the marchers.

“Will we forget our martyrs’ blood?”

“No!”

“Will we compromise for peace?”

“No!”

Behind the trucks swelled a larger pack of mourners. They carried flags, hundreds of them, representing every political faction in Gaza — Popular Front flags and Fatah Youth flags and Islamic Jihad flags; flags with images of clenched fists and crossed rifles and soaring minarets — and they marched in a mass that stretched from sidewalk to sidewalk, and anyone standing and watching had the choice of joining the demonstration or being trampled by the flow.

At the crowd’s core were the three bodies. They were laid out on gurneys, wrapped in Palestinian flags, flowers piled on their chests, riding atop the crowd. Up close, I noticed that Ahmed did not have the jet-black hair typical of a Palestinian. It was slightly red. His eyebrows were thick and caterpillery. His left ear, the only one visible (the right one, presumably damaged, was covered by a head cloth), stuck out like an open door. He seemed to be sweating. Perhaps it was the mortician’s makeup, melting under the heat.

The marchers pressed toward Martyrs’ Cemetery, a simple expanse of sand dotted with headstones and fenced by palm trees. Three fresh graves had been dug, and mourners packed around them. Women tipped their heads skyward and keened in trilling strains. Men linked arms and swayed forward and back. A mullah stood in the center, among the graves, and as the bodies arrived he shouted, “With our soul, with our blood, we will sacrifice ourselves for God.” He shouted it again and a third time, and the crowd picked up the chant. The three boys were slid into the ground and the dirt was piled on, a thousand hands pawing at the graves. After the bodies were covered, the mounds atop their graves were a collage of palm prints, and everyone was still chanting, even the smallest of children, who wandered about the cemetery dazed from the excitement, repeating the words softly to themselves.

—

As the funeral ended there seemed to be a general exodus in the direction of Karni Crossing, a short walk away. Toward the rear of the battlefield, a few hundred yards from the Green Line, rose several large mounds of dirt, almost a miniature mountain range. These were the equivalent of the battle’s grandstands, and the hills were heavy with spectators, about half teenagers and half older, a hundred people milling around, arguing politics and charting the progress of the clashes. At moments when the situation became hazardous, everyone retreated from the hilltops and stood behind the dirt, and the discussions scarcely missed a beat.

In front of the dirt mounds, closer to the Green Line, were a series of cement blocks, about the size of dishwashers, each pocked with bullet scars and protecting a small clot of fighters. A few broken blocks hid just a single person, a fighting force of one. At the very front, about thirty yards from the Green Line, were a series of wide trenches cut into the soft desert soil, protected by dirt walls. The trenches were jammed with dozens of stone-throwers, almost all of them high-school age or younger. At the Green Line itself, on the far side of the fence, were three Israeli armored trucks and one tank, driving back and forth. Soldiers poked out the top hatches, rifles poised. There were no Israeli soldiers outside of the vehicles, at least none visible. A dog had been killed the day before, and its corpse lay on the battlefield, infusing the trenches with a miasmic tang. Plastic bags caught in the razor wire flapped in the wind. A burning tire exhaled black columns of smoke.

The area was wide open — there were heaps of uprooted tangerine trees, a mess of twisted steel where a factory once stood, and the remains of a demolished house. The Israeli Defense Force’s policy is to bulldoze any spot on a battlefield that might offer protection to Palestinians. But instead of being deterred, the fighters who show up each day face an increasingly greater risk. At Karni, no one I spotted anywhere near the front carried a gun. The ten or so Palestinian soldiers I saw were all well back, at the dirt mounds, their weapons slung casually over their shoulders. “We don’t fire our weapons during the day,” one of them explained. The children were the warm-up act. At dark, the real fighting began — soldiers against soldiers. Several Israeli officers confirmed that virtually all the shooting from the Palestinian side occurred after nightfall.

Most of the stone-throwers at the front, it seemed, lived in refugee camps. Still, even in the trenches, the boys wore collared shirts, school-uniform pants, and stylish sneakers; Palestinians are fastidious dressers, no matter the occasion. Toward the rear, kids in leather belts and jean jackets and penny loafers crouched safely behind the dirt mounds, too far from the Green Line to throw stones. The boys in the back were nearly all from the more middle-class neighborhoods outside Gaza City. Their parents were carpenters and electricians and merchants. They had clean fingernails and careful haircuts; they owned watches and portable radios.

At the back there were vendors selling soft drinks and ring-shaped loaves of bread and, from a cart beneath a red umbrella, flavored ices. Bicycles and book bags were scattered about. A boy sat cross-legged in the dirt, studying from a mathematics book. Another boasted about his personal computer, which housed, he said, a photo collection of women in bikinis — okay to keep, he explained, because the women weren’t Islamic. Eight ambulances, with red crescent moons painted on the sides, were lined up like cabs at an airport, the drivers socializing and smoking. Parked nearby were two dump trucks, property of the Palestinian security services. At sunset the trucks would roll onto the battlefield and the kids would scramble aboard, to be driven back to their neighborhoods as if riding the school bus.

—

What was missing was anger. Even in the trenches, even while throwing stones, none of the boys seemed particularly enraged. If anything, they appeared to be having fun. Yehya and Rami, two of the kids who had known Ahmed, spent half an hour assembling an enormous slingshot that required both of them to operate. They called it a Palestinian tank. Nobody cared that its accuracy could at best be considered random. Anyone who found a soda bottle would rush off and soon return with it half-filled with gasoline, a rag stuffed in the neck. The rag would be lit and the bottle tossed, to trenchwide cheers. It usually landed nowhere near an Israeli soldier. The Gaza soil never seemed short of rocks, though once in a while a donkey cart laden with cinder blocks would arrive and the boys would race to the cart, smash the blocks and return to the front with armloads of fresh ammunition. During the frequent cigarette breaks, the preferred brand was Marlboro, because if you took a pack and turned it upside down, the word “Marlboro,” when inverted, looked a little bit like the phrase “Horrible Jew.”

Not one Palestinian political faction, no matter how militant, claims that it encourages children to participate in the clashes. Every party’s official position is that it’s better for the children to stay home. But if the boys decide on their own to fight, the organizations all say, well, there’s nothing we can do to stop them — this is a popular uprising, after all, and the children, like the rest of us, feel strongly about recapturing our homeland. At the front, the boys themselves could not say precisely who or what had motivated them to fight. They were too young to be affiliated with a political party, though most knew their parents’ party, which was overwhelmingly Hamas, the fundamentalist movement that denies Israel’s right to exist. Nobody told them to come, the boys all affirmed. They saw images on television, they said, or joined a demonstration, or knew a friend who fought. There were no recruitment drives or strategy sessions or battle plans. They were just here to throw rocks. It was better than going to school.

Of Ahmed’s six friends at the front, two claimed that their fathers had granted them permission to fight, and all said that their mothers forbade it. It’s not uncommon to witness a mother arrive at the front, spot her child and haul him off with an arm grip that indicated further punishment to come. About five percent of boys under eighteen in Gaza regularly join the clashes, more than enough to compose a potent fighting force.

“If my mother knew I was here,” said Sameh, “I’d be beaten.”

“I told my mom I’m playing soccer,” said Yehya.

“Mine thinks I’m at Aymen’s house,” said Hares.

“And mine thinks I’m at his house,” said Aymen, and everyone broke into laughter.

When they tried to explain exactly why they were throwing stones, everyone said the same thing — not approximately the same thing, but exactly the same thing. “I’m fighting for Palestinian freedom,” they said. “I’m fighting so that Jerusalem can be the capital of Palestine. I’m fighting because the Jews stole our land and we want it back.” Every sentence was taken, verbatim, from messages played and replayed on Palestinian TV.

At one point, following a rock-throwing jag, there was a sudden series of suctionlike pops. “Fireworks!” the kids shouted, and in an instant tear-gas canisters exploded about us. For reasons that didn’t seem clear, the Israeli retaliation had begun. No one panicked. The boys reached into their pockets and produced cotton balls that had been rubbed with garlic and onion and pressed them to their eyes. Aymen tore his in two and gave half to me. Then the games began. Several boys vaulted out of the trenches, ran to the steaming canisters, picked them up and hurled them back at the Israelis. They were playing with army men, just as I did at their age, only mine were plastic and theirs were real.

Canisters that had already discharged their gas were brought to the trenches so the boys could play hot potato, staging contests to see who could hold the scalding metal in their fingers the longest. “Look,” said Hares, making a face. “Built in America. I hate America.” The writing on the outside of the 560 CS Long-Range Projectile said that it was manufactured by Federal Laboratories in Pittsburgh. When it had sufficiently cooled, Hares stuffed it in my pocket. Everyone was working on an ammunition collection. A basic set included the two styles of rubber-coated bullets (spherical and cylindrical), an M-16 bullet, a tear-gas canister, and a .50-caliber bullet. Sometimes the kids traded them back and forth, like baseball cards.

—

Shortly after the tear-gas attack, which inspired nobody to leave the front, came rubber-coated bullets. Two, three, four shots. These were the spherical ones — musket-type balls sheathed with a few millimeters of cushioning. They’re fired from high-powered rifles; boys have died from being struck in the head by them. They ricocheted unpredictably about the trenches, and the boys hunkered down and the atmosphere turned a notch serious. A few people began crawling toward the rear of the battlefield, though all of Ahmed’s friends remained. Muhammad curled himself into an insectlike ball and bit down hard on his lower lip. Sameh lay on his side and knocked two stones together, tapping out a jittery beat. Hares retrieved one of the bullets, stuck his fingernail into the rubber, peeled it like an orange, put the metal ball into his slingshot, and fired it back.

Despite the scare, the next time an armored car approached, nearly everyone jumped up and launched an especially exuberant barrage of rocks. The boys, so far as I could tell, were convinced that their stones would eventually disable the Israeli Army. This may one day prove correct, though probably not in the David-versus-Goliath fashion the boys envision. What’s clear to many Palestinian leaders but not apparent to the children is that the stones, and those who throw them, are playing an almost purely symbolic role in the war. In Mecca, Muslims throw stones at a statue representing the Devil; it’s a centuries-old tradition. In Gaza, Israeli soldiers fill the Devil’s role. Stones, the Palestinian leaders know, won’t directly defeat the Israelis, but repeated images of rock-throwing youths being shot by highly trained soldiers might turn international opinion against Israel and persuade other Arab nations to join the war. In this way, Palestinian thinking goes, Israel could be defeated and erased from the map, replaced with the nation of Palestine.

After about ten rubber shots in five minutes, a real bullet was fired. Again, it wasn’t clear why. No vehicle seemed to require access to the Karni Road; nothing more lethal than rocks, as far as I could tell, was coming from the Palestinian side. I knew it was a live bullet because the sound was different — just a hummingbird’s whoosh and a quick spray of sand — and because every boy’s eyes instantly popped wide open. But the proof came with the second shot. There was another whoosh, followed by a moment of strained silence, everyone’s shoulders instinctively hunched, and then a choking gasp that swiftly accelerated into an agonized cry. Someone was hit. A few feet down the trench there was a burst of whistling and yelling, and a dozen boys raced to the spot. Hands grabbed for the body. The wounded boy was hoisted out of the trench, dropped once, then picked up again and carried into the open. His right thigh was bent in an unnatural way. Blood blossomed on his pants. There was the sound of spinning wheels; a siren.

The Israeli Defense Forces have an official rule of engagement: Live ammunition is never to be used unless Israeli soldiers or the people they are protecting are in immediate danger. The situation at Karni crossing, it was explained to me by an army spokesman, fell under this definition. Thrown rocks, I was told, have killed motorists. And for a few hundred Israelis, the Karni Road was their only link to the outside world. Israeli settlers have the right to drive. Palestinian children refuse to vacate the road. Something has to give.

I spent two weeks at Karni during daylight hours, and in my time there, the Israeli Army fired live ammunition almost every day. Sometimes only two or three shots, sometimes a dozen or more. On occasion the shots were fired when cars or buses needed to enter or exit the settlement, at other times I could ascertain no reason for the shooting. Not once did I see or hear a single shot from the Palestinian side. Never during the time I spent at Karni did an Israeli soldier appear to be in mortal danger. Nor was either an Israeli soldier or settler even slightly injured. In that two-week period, at least eleven Palestinians were killed during the day at Karni.

When the ambulance arrived, the wounded Palestinian was pushed inside, and in the commotion I hopped in as well and we sped away. The stone-thrower, an eighteen-year-old named Ibrahim Abusherif, arched his back and clenched and unclenched his fingers and shouted a single phrase over and over: “Damn the Jews; damn the Jews.” His right femur, the medic said, appeared to be shattered. The ambulance rattled across the dirt and onto the cracked pavement, and the bottles and bandages and intravenous bags slid about on their little shelves, and Ibrahim continued to damn the Jews.

At Shifa Hospital, he was hurried into the emergency room and laid on a bed beneath a bare, flickering bulb. The floor was made of rubber tiles, sticky with the blood of previous patients. Elsewhere in the emergency room, behind salmon-colored curtains, were six other injured fighters — a handful of the forty people who were injured, on average, each day in the clashes in Gaza. The hyperventilated gasps of earnest pain filled the room. On the wall was a poster of a suicide bomber who had blown himself up two weeks before. Written above the poster, in thick black letters, were the words, “He is worth a thousand men.” A doctor dug into Ibrahim’s thigh and removed three twisted fragments of an M-16 bullet, which he held up like trophies. Then Ibrahim was rolled into surgery.

—

Rimal Boys’ School, the school that the two slain classmates attended, is hidden behind a stout cinder-block wall, insulated somewhat from the filth and clamor of Beach Camp. The entrance is a large steel door, upon which was spray-painted “The Student Union Congratulates Our Martyrs.” The school’s headmaster guided me to one of Ahmed’s former classrooms. Forty-four students, all boys, sat two to a wooden desk. (Palestinian girls attend their own schools and rarely appeared at the clashes.) The rear wall was decorated with six posters of Ahmed, two posters of Ibrahim, and a detailed drawing of a human cell, with the nucleus and cytoplasm and mitochondrion labeled in Arabic. Muhammad, the boy I’d met in the trenches, flashed me a brief, acknowledging smile, then propped his head in his left hand and focused on his book. Ahmed’s desk, in the second-to-last row, had been turned into a shrine, decorated with a flag and a head scarf and a bouquet of plastic flowers.

Palestinian schoolbooks tend to offer a rather one-sided view of Middle Eastern history. In some texts, Nazism and Zionism are equated, and Palestinians are portrayed as the true historical stewards of the land. Maps of the region omit Israel entirely and label the land between Lebanon and Egypt as Palestine. A widely studied book, “Our Country Palestine,” states that “the Jewish claim to historic rights to Palestine has no justification; it is a deceitful and disproved claim with no parallel in history, a blatant lie.”

Every student I spoke with, in the hallways, in classrooms, in the courtyard, insisted that he, too, wanted to be a martyr. “I don’t fear the bullets,” one boy informed me. “I want to be with God,” said another. “I will avenge Ahmed and Ibrahim’s deaths,” announced a third. This was, I suspected, a form of adolescent bluster, but no one would dare say anything different, especially in front of his friends. In the school’s art room, though, the pictures on the walls offered a different perspective. The works were done in colored pencils, and they were nearly all fantasies — not of violence, but of moments of almost profound simplicity: a family picnicking on a beach; two boys on a swing set; a tennis game on a tree-shaded court.

When school ended for the day, Muhammad agreed to let me walk home with him. Immediately outside the school’s gate, he unbuttoned his school shirt to reveal an undershirt advertising his favorite musician, an Iraqi singer named Kazem el-Saher. At a record store he stopped and gazed at some of el-Saher’s albums, but he didn’t have any money. Muhammad walked with a teenager’s slack-legged gait, strolling along one of Beach Camp’s central thoroughfares, which had a V-shaped notch running along the middle, transporting raw sewage to the sea. Beach Camp’s idyllic name was bestowed because it abuts the Mediterranean, but the beaches were little more than garbage dumps.

There are no real side streets in Beach Camp, just alleys between the homes so narrow that people can pass one another only by turning sideways. The alleys were a cat’s cradle of laundry lines, flush with school uniforms. The houses, concrete cubes with corrugated tin roofs, were packed together and stacked atop one another as if in a warehouse. Trash whirled about. In a vacant lot a few cactus bushes pushed through the sandy soil. Women shuffled their feet listlessly, hauling loads of laundry. Unemployed men sat around playing backgammon. The air smelled of fried fish and charred rubber and fresh mule dung. Small children, many of them barefoot, ran about in hyperkinetic herds, sometimes tossing rocks at one another, or playing marbles, or lighting cardboard fires. Older kids played soccer in the street. The average woman in Gaza gives birth seven times.

A vegetable stand sold a shopping bag’s worth of tomatoes for the equivalent of a quarter. Gaza’s borders had been sealed by the Israeli Army since the start of the violence — the strip was now, for all practical purposes, a million-inmate prison. Even the internet had been disrupted. Farmers, who worked humble plots in the few uncrammed corners of Palestinian-controlled Gaza, were prohibited from exporting goods, creating a glut. Most of the season’s crops were expected to rot.

Graffiti was everywhere, on the walls of homes and shops and abandoned construction sites. Teams of painters, employed by each of the major political factions, were working daily, whitewashing old slogans and adding new ones, and for those without television or radio, the messages (“On With the Intifada”; “To Jerusalem We Are Going”) served as daily updates on the mood of the Palestinian leadership. At Beach Camp’s entrance, an Israeli flag was painted on the roadway and both sidewalks, so that anyone passing through had to step on it. Most pedestrians made sure to plant a foot in the center of the six-pointed star.

—

Muhammad was one of fourteen children — seven brothers and seven sisters. His father, Tayser, was a janitor at Shifa Hospital; his mother, Anaam, owned a tiny shop next to their home. Their family name is Saman. Like many Muslims, Muhammad prayed five times a day, though he said he wasn’t especially religious. He attended mosque on Fridays, at a new building in Beach Camp where the sermons were usually laced with anti-Jewish screeds. He had never listened to rap music, or eaten at McDonald’s, or heard of e-mail.

He slept on a reed mat in a room with eight of his siblings. He woke at six o’clock in the morning and ate a bit of cheese and falafel — “unless I wake up late; then I just run to school.” In the rear of his mother’s shop, in a metal cage, he kept his pet birds, a dozen canaries. “I like the way they look and I like the way they sing,” he told me. Muhammad had recently marked his fifteenth birthday but hadn’t received any presents. The last gift he’d been given was nearly a year before, to mark Eid al-Fitr, the post-Ramadan feast. His mother bought him a new pair of pants, the ones he was now wearing, which were too long and rolled at the ankles. In school, he was good at math and carpentry and not that solid in his foreign language, which was English.

Muhammad had never once in his life left the Gaza Strip. Yet when asked where he was from he’d respond, as many in Gaza do, with the name of a town on the other side of the Green Line. His family left Hamama in 1948, soon after Israel declared its statehood, a period during which tens of thousands of Palestinians relocated to Gaza, which was then under Egyptian control. Gaza was captured by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War, and the Jewish settlements were soon established. Muhammad’s parents have told him stories about Hamama — though they, too, have never been there. “It’s a small town,” Muhammad told me. “It’s filled with olive trees. There are big fields, and the soil is good. The water is good. It’s healthy to live there.”

If Muhammad had the power to end the conflict, this is what he’d do: “I’d give Palestinians back all of their homeland, and I’d send the Israelis to the countries they came from.”

And if the Israelis refused to leave?

“Then I’d kill them.”

I asked Muhammad what he’d buy if he had money. “A gun,” he said. The previous two summers, he added, he’d attended a sleep-away camp where he’d learned to shoot M-16s and Kalashnikovs, firing at targets dressed up like Israeli soldiers. The camp was financed by the Palestinian National Authority, the governing body of the Palestinian-controlled areas of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. As soon as he turned sixteen, he told me, he planned to join the Palestinian security services.

What would you buy, I asked him, if you could purchase more than just a gun?

“I’d buy a tank,” he said.

But what if there were peace? Then what would you buy?

Muhammad thought for a second. He looked upward, as if calculating something, then grinned in a way that involved his entire face. “I’d buy a bicycle,” he said. “A mountain bike. I’d buy a cell phone. I’d buy a bed, and a bedroom, and a desk, and a soccer ball. And a TV. And chocolate. I’d buy a lot of chocolate. I love chocolate.”

—

On the way to Muhammad’s house, we stopped at Martyrs’ Square, the centerpiece of Beach Camp, where a plaque listed seventy-three names of men and boys from the camp who have died fighting the Israelis. A ceremony known as a “martyr’s wedding” was being held for Ahmed and Ibrahim. A large green tarp had been stretched over much of the square for the three-day celebration. Men sat in plastic chairs, drinking coffee and smoking apple-flavored tobacco from elegant water pipes. There were streamers hung with miniature Palestinian flags, and a disk jockey played the theme music of the uprising, most notably “Jerusalem Never Dies,” by the Egyptian singer Hani Shaker. Here, the graffiti reached critical mass; every political group had painted a sign congratulating Ahmed and Ibrahim for dying in the service of God. There were a pair of billboard-size murals, one of a burning Israeli flag, the other of a young boy hurling a stone. Kids jumped around on the empty chairs. A banner flew overhead, courtesy of the Popular Liberation Front: “If You Want to Die — Die a Martyr, Amid the Bullets.”

The festival felt neither weddinglike nor funereal. It was odd, stilted, like an ill-rehearsed play. Ahmed’s father, Sliman, was sitting in the center of the square fingering a strand of prayer beads. People were all around him, yet he appeared to be alone. He had a gray mustache and a drawn face and curly hair, tinted with some of the red I’d seen in Ahmed’s hair. “I’m proud of my son; he fought for our homeland,” he said, avoiding eye contact, his voice a monotone. “He was very brave. A very brave boy.”

The women gathered at the family home, one street away. Ahmed had seven brothers and two sisters, all of whom lived in two underfurnished rooms. Ahmed’s mother, Afaf, sat cross-legged in her black robe, clutching her son’s book bag, surrounded by friends and relatives. There was an old yellow refrigerator in the corner and a ceiling fan overhead, but no electricity. A tray of dates served as refreshments. Unlike Ahmed’s father, Afaf was animated and emotive and loud. What she said, though, bore no relation to what she was asked. She was simply chanting phrases. “I am proud,” she said. “So proud. Look at how beautiful his wedding is. What a grand celebration. Thanks be to God. Did you see how his face shone? Oh, he is still alive! I will give all my children, if that’s what it takes to get our homeland back. All of them can become martyrs. It will be a dignity to me.”

At Karni Crossing, several of the boys casually mentioned that dying would not only transport them to paradise, it would also bring riches to their families. When a Palestinian, no matter his age, was martyred in the clashes with Israelis, the Palestinian National Authority issued a one-time payment of $2,000 to his family, followed by monthly payments of $150 that continued until the last child had left the house. The Red Crescent, an Islamic relief organization, contributed an additional $2,500. And the government of Iraq donated $10,000 to every martyr’s family. Saddam Hussein had pledged $4.5 million to the Palestinian Authority — enough to cover 450 martyrs — and Gaza newspapers frequently ran ads from martyrs’ families thanking the Iraqi leader for his largess.

Ahmed’s father told me that the Palestinian Authority’s payment had already been delivered. The $2,000 came in an envelope, in United States currency. He was expecting the rest of the money in a matter of days. The first thing he planned to purchase, he said, was a set of Korans imprinted with Ahmed’s name. He’d distribute them to his friends in Beach Camp. Next, he’d buy a carpet for the mosque. Finally, he said, with the remainder of the money, the family would buy a house. “We are twelve people living in two rooms,” he explained. He said he was looking for a little plot of land, where the family could grow olive trees. This is what Ahmed would have wanted, he mentioned. The father had been unemployed for some time and said that there was no other way the family would ever be able to leave Beach Camp.

“Ahmed always asked why we couldn’t move out of this camp and have a nice house,” he said. “Now we can.” His wife, he added, was pregnant. The notion of an impending birth caused him to pause and, for the first time during our conversation, look directly at me and smile. “If it’s a boy,” he announced, “we’ll name him Ahmed.”

—

Muhammad’s home is a few steps from Martyrs’ Square, down one of Beach Camp’s narrow alleys. There were three rooms, two with dirt floors covered by rattan mats and one with a cement floor overlaid by a flowered carpet, the family’s most valuable possession. The kitchen consisted of a few aluminum pots and a tiny propane stove, like one that might be used on a camping trip. There was no furniture. All of the family’s clothes were kept in suitcases or plastic bags, as if, after fifty-two years, they still hadn’t decided to move in.

Anaam, Muhammad’s mother, was sitting in her store, a windowless box that sold soda, candy, eggs, flour, teacups, and tampons. She wore a black-and-white checkered head cloth and a brick-red robe; her five-year-old daughter, Esraam, sat on her lap. The store was a popular place, mainly because neighborhood kids knew that they could stop by after school and Anaam would give them each a free piece of candy. There was electricity and a television, which was perpetually tuned to the Palestinian network, where endless images of Israeli soldiers’ brutality accompanied a soundtrack of nationalistic songs. Muhammad and I slipped behind the counter and sat down.

“You know,” said Muhammad’s mother, gazing at her son, “he goes to sleep scared and he wakes up scared.” Muhammad sunk into his seat and rolled his feet on edge. When a friend of his stopped by a minute later, he made his escape. Anaam kept talking. She explained what happened to Raed, her oldest son. Raed was twenty-eight years old. In 1995, he was shot in the mouth while stoning Israeli soldiers. The family couldn’t afford dental work, so he still had no teeth. Then she told me about her husband. It was a few months before Raed was shot, during a time the Israelis had imposed a strict curfew on Gaza. Her husband heard the five a.m. call to prayer and decided, defiantly, to walk to the mosque. A group of five soldiers caught him just outside the house and began beating him. The family rushed out to see what was happening. Muhammad watched as the soldiers broke his father’s right arm with a billy club. He watched as they pounded his legs. “He started screaming: ‘My dad is dying! My dad is dying!’” said Anaam. “He wanted to go after the soldiers, and I had to hold him back. I had to tell him no, you can’t go after them.”

Ever since then, she said, Muhammad has harbored a frightening anger. “He’s told me, ‘Mom, I’ve had enough of this life,’ and it’s made me scared. I’ve told him: ‘Muhammad, please don’t. You’re too young. You’re still a child.’ But when the boys see their friends killed, they get angry, and they go to the clashes. Even if he’ll go to heaven, no mother wants her child to die. I’ve told him that throwing stones at Jews will not make him a martyr. I’ve told him the real sacrifice is staying at home and helping care for his family. If you die doing that, I said, then you’re a real martyr. I’ve told him that if he goes to the front and dies, then I’ll be angry at him, and you know how God is — God will never accept your martyrdom if your mother is angry at you. He said, ‘Okay, Mom, I’ll stay.’ But every time he asks for a shekel I’m worried that it’s for a taxi to go to the clashes. I worry that the neighbors will come by and say, ‘Congratulations, your boy is a martyr.’ The last two days, since Ibrahim and Ahmed have gone, I’ve just sat and looked at him, at how beautiful he is.”

And then she pulled her scarf over her eyes and began to sob.

—

I found Muhammad just down the alley from the store, playing marbles with his friend. He’d taken his bird cage out, and his canaries were basking in a bit of sun. It was late in the afternoon, and the shadows were long. There was a clanging of the water truck’s bell, and the neighborhood women grabbed their containers and headed into the street. The sky held the contrail of an Israeli fighter jet; on patrol, as always. Muhammad looked at me with a crooked face and asked if I told his mom that he’d gone to the clashes. I shook my head no. He shifted closer and whispered that he’d once stolen a shekel from the shop’s till, so that he could take a cab to Karni Crossing. I said that his mom would be very upset, and he said that he knew.

“Are you sure,” I asked, “that you want to be a martyr?”

“Yes,” he said. “I want to be a martyr.”

“Do you know what that means?”

“Throwing stones and Molotovs.”

“No” I said, curious. “That’s not what it means. It means dying.”

“I’ll take a bullet in the leg,” he said.

“That doesn’t make you a martyr. You would have to take one in the head.”

“My brother was shot in the head.”

“To be a martyr,” I said, “it has to go all the way through. Are you sure you want to be a martyr?”

“No,” said Muhammad. “I want to be an architect.”

— end —