These are my final words: “Why a camp chair?” I speak them to a man named Wade. Wade from Minnesota. I’m in line behind him, waiting to enter the Dhamma Giri meditation center, in the quiet hill country of western India, for the official start of the 10-day course. Wade tells me that this is his second course and that he learned a valuable lesson from the first. “I’m so glad I have this,” he says, indicating the small folding camp chair tucked under his arm. I utter my last question. It’s never answered. One of the volunteers approaches, puts a finger to his lips, and the silence begins.

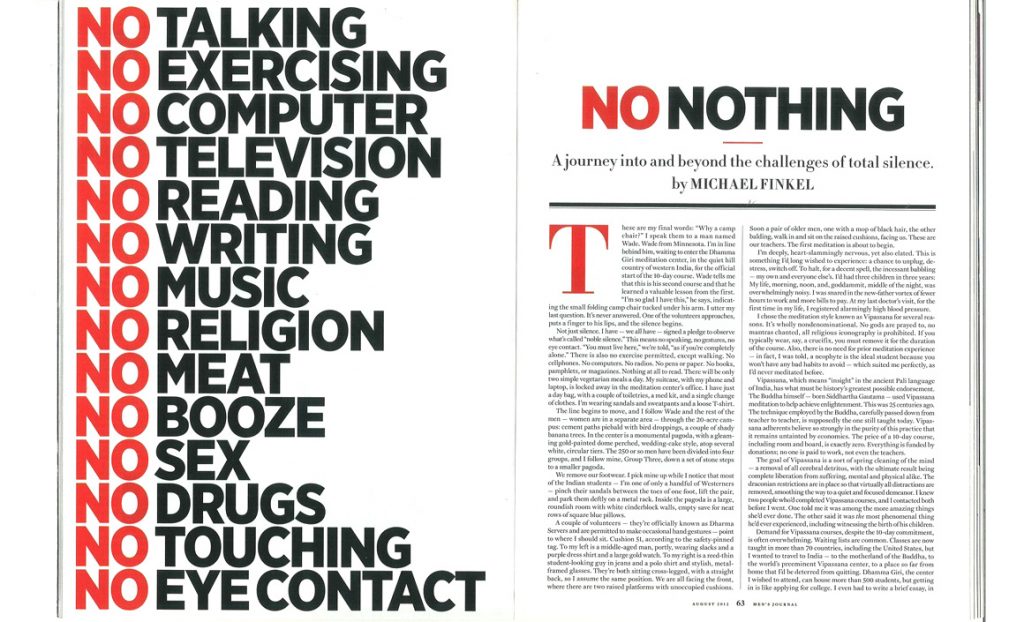

Not just silence. I have – we all have – signed a pledge to observe what’s called “noble silence.” This means no speaking, no gestures, no eye contact. “You must live here,” we’re told, “as if you’re completely alone.” There is also no exercise permitted, except walking. No cellphones. No computers. No radios. No pens or paper. No books, pamphlets, or magazines. Nothing at all to read. There will be only two simple vegetarian meals a day. My suitcase, with my phone and laptop, is locked away in the meditation center’s office. I have just a day bag, with a couple of toiletries, a med kit, and a single change of clothes. I’m wearing sandals and sweatpants and a loose T-shirt.

The line begins to move, and I follow Wade and the rest of the men – women are in a separate area – through the 20-acre campus: cement paths piebald with bird droppings, a couple of shady banana trees. In the center is a monumental pagoda, with a gleaming gold-painted dome perched, wedding-cake style, atop several white, circular tiers. The 250 or so men have been divided into four groups, and I follow mine, Group Three, down a set of stone steps to a smaller pagoda.

We remove our footwear. I pick mine up while I notice that most of the Indian students – I’m one of only a handful of Westerners – pinch their sandals between the toes of one foot, lift the pair, and park them deftly on a metal rack. Inside the pagoda is a large, roundish room with white cinderblock walls, empty save for neat rows of square blue pillows.

A couple of volunteers – they’re officially known as Dharma Servers and are permitted to make occasional hand gestures – point to where I should sit. Cushion 51, according to the safety-pinned tag. To my left is a middle-aged man, portly, wearing slacks and a purple dress shirt and a large gold watch. To my right is a reed-thin student-looking guy in jeans and a polo shirt and stylish, metal-framed glasses. They’re both sitting cross-legged, with a straight back, so I assume the same position. We are all facing the front, where there are two raised platforms with unoccupied cushions. Soon a pair of older men, one with a mop of black hair, the other balding, walk in and sit on the raised cushions, facing us. These are our teachers. The first meditation is about to begin.

I’m deeply, heart-slammingly nervous, yet also elated. This is something I’d long wished to experience: a chance to unplug, de-stress, switch off. To halt, for a decent spell, the incessant babbling – my own and everyone else’s. I’d had three children in three years: My life, morning, noon, and, goddammit, middle of the night, was overwhelmingly noisy. I was snared in the new-father vortex of fewer hours to work and more bills to pay. At my last doctor’s visit, for the first time in my life, I registered alarmingly high blood pressure.

I chose the meditation style known as Vipassana for several reasons. It’s wholly nondenominational. No gods are prayed to, no mantras chanted, all religious iconography is prohibited. If you typically wear, say, a crucifix, you must remove it for the duration of the course. Also, there is no need for prior meditation experience – in fact, I was told, a neophyte is the ideal student because you won’t have any bad habits to avoid – which suited me perfectly, as I’d never meditated before.

Vipassana, which means “insight” in the ancient Pali language of India, has what must be history’s greatest possible endorsement. The Buddha himself – born Siddhartha Gautama – used Vipassana meditation to help achieve enlightenment. This was 25 centuries ago. The technique employed by the Buddha, carefully passed down from teacher to teacher, is supposedly the one still taught today. Vipassana adherents believe so strongly in the purity of this practice that it remains untainted by economics. The price of a 10-day course, including room and board, is exactly zero. Everything is funded by donations; no one is paid to work, not even the teachers.

The goal of Vipassana is a sort of spring cleaning of the mind – a removal of all cerebral detritus, with the ultimate result being complete liberation from suffering, mental and physical alike. The draconian restrictions are in place so that virtually all distractions are removed, smoothing the way to a quiet and focused demeanor. I knew two people who’d completed Vipassana courses, and I contacted both before I went. One told me it was among the more amazing things she’d ever done. The other said it was the most phenomenal thing he’d ever experienced, including witnessing the birth of his children.

Demand for Vipassana courses, despite the 10-day commitment, is often overwhelming. Waiting lists are common. Classes are now taught in more than 70 countries, including the United States, but I wanted to travel to India – to the motherland of the Buddha, to the world’s preeminent Vipassana center, to a place so far from home that I’d be deterred from quitting. Dhamma Giri, the center I wished to attend, can house more than 500 students, but getting in is like applying for college. I even had to write a brief essay, in which I pleaded that I was desperate to “capture a greater degree of calmness in myself.” A few weeks later, via email, I learned I’d been accepted for a spot in the February 2012 class. So I left my wife and kids and flew to Mumbai.

—

Now, folded atop my royal-blue cushion in the crowded room in the small pagoda, facing the teachers, I wait. I don’t quite know what to do. It’s evening; there are no windows in the meditation room, but there’s ambient light, gradually waning. Spiderwebs are hammocked about the ceiling. I glance at the teachers; they’re motionless, eyes closed. I look at my neighbors. Eyes shut. I close my own. I listen to the birdcalls, intense beyond the pagoda’s walls. There’s the scent of a burning bug coil. Someone burps.

Finally, I hear a noise in the front of the room, a slight rustle. I can’t help but peek. One of the teachers, the balding one, presses a button on a portable CD player. A gravelly voice flows through several wall-mounted speakers. First in Hindi, then English. It’s the voice of S.N. Goenka, who is credited with Vipassana’s current resurgence. Vipassana had faded from use in India a few centuries after the Buddha’s death. But it thrived in Burma, where Goenka stumbled upon the technique in the 1950s. Though a successful businessman, he suffered from debilitating migraines that no mainstream doctor could alleviate. Vipassana not only ended his headaches, it infused him with a deep sense of bliss. His motto – “Be Happy!” – is stenciled on dozens of signs across the Dhamma Giri campus.

Goenka eventually abandoned his business pursuits in order to share what he’d learned. In 1969, he traveled to India and reintroduced Vipassana to the land of its origin. In a nation sharply divided by caste and religion, Vipassana welcomed people of every background. The meditation technique fanned across the subcontinent and then, driven by word of mouth, spread throughout the world. Goenka is now too old to teach in person, but his recorded instructions and videotaped lectures are used in all Vipassana centers – every course, in every country, is highly coordinated, right down to specific meditating and sleeping hours.

The voice, Goenka’s voice, tells me to think about my nostrils. To focus all my attention on my respiration. On the air flowing out. Flowing in. Is it predominantly coming from my left nostril? My right? Both equally? Ponder it, says Goenka. Feel it. Concentrate.

That’s all. The teacher shuts off the CD player, and the room falls silent. I sit, eyes closed, focusing on my breathing. I am, in fact, a predominantly right-nostril man. Which I find interesting. Sorta. For a few minutes.

I had steeled myself, over the weeks leading up to the trip, for an intense mental challenge. My plan was to give Vipassana a serious and thorough try, though I was aware it was unlikely to be an easy fit. I don’t think anyone has ever described me as a natural-born meditator. I’m loud. I’m energetic. I’m spazzy. I crave constant stimulation. “As soon as you finish breakfast,” one of my friends predicted, “your only thought will be ‘What’s for lunch?’ ” But I’d reached the age – I’m 43 – at which becoming a little more contemplative, a little less chicken-without-a-headish, might serve me well. My doctor had said as much.

In other words, I am prepared to be bored. What surprises me – what I haven’t envisioned – is meditation’s physical aspect. The last time I sat on the floor, without back support, for an extended period of time was probably kindergarten. Minutes into Goenka’s nostril assignment, my lower back is throbbing. Also my hips. My knees. My neck. I shift position. I refold my legs. I forget about my breathing. All I can feel is the pain.

Fortunately, it’s an extremely brief meditation session. Less than half an hour. Still, it’s long enough to worry me. The balding teacher – Yogesh, he tells us, is his name – picks up a microphone and calmly informs us that the real meditation starts tomorrow. We’re dismissed to our rooms.

We rise, file out of the pagoda, engage in a silent sandal-retrieving scrum, and scatter along the cement paths, dark now beneath a half-moon, past the central pagoda dotted with lights – all of us shuffling about as if in a zombie movie. The breeze tinkles a few chimes. The canoe-size banana leaves create a pleasing susurrus. I’m a little hungry.

I’ve been assigned a private room in a cluster of shoe-boxy buildings near the campus’s barbed-wire-topped perimeter wall. The room has white walls, a white bed table, a white ceiling fan, and a white toilet. It’s illuminated by a single flickery, low-wattage bulb. The bed is a thin mattress atop a plank of wood. It’s purposely uncomfortable. According to the Vipassana Code of Discipline, which we’ve all vowed to follow, in addition to no dishonesty or stealing or taking of any intoxicants or engaging in any sexual activity, we also promised not to sleep in “luxurious beds.” Sleep deprivation is apparently an integral part of purifying the mind. I lie on the bed. It is, indeed, not luxurious. I flip off the light. I hear the buzzing of mosquitoes, which reminds me of another rule in the Code: no killing any being. I let them buzz.

I’m tired from travel – the three-continent trip to Mumbai, the packed train north to the village of Igatpuri, the uphill walk to Dhamma Giri – and my cravings for a mind-easing book or television show or album swiftly dissipate. I drift to sleep.

—

My head has been stuffed inside an enormous drum. And now someone’s pounding on it. Or, rather, no. My head is right here. I’m still in bed. But the booming is real. It’s a gong, an incredible gong, rolling like thunder through the night. I glance at my watch: 4 am, on the nose. Wake-up time.

I stand. My back – from the meditation, from the bed – gives me a cranky greeting. I flip on the light. Son of a bitch. I’m bitten to all hell, my chest and arms and shoulders a crazy domino game of red dots. I splash cold water on my face and walk back to the Group Three pagoda.

I’m looking forward to learning the next step, beyond contemplating my nostrils. But no teachers arrive, just students. There are no further instructions. And I can’t ask anyone what I’m supposed to do. So I sit, striving to keep my mind free of distractions. I detect the tide of my respiration flowing over my upper lip – cooler entering my nose, warmer exiting. Still favoring my right nostril.

A line from The Big Lebowski jumps to mind. You want a toe? I can get you a toe. Then a song refrain. A dozen of them, as if I’ve pressed scan on my car radio. This is Ground Control to Major Tom. Snippets of sitcom dialogue, a phrase from a Richard Brautigan poem, famous opening lines – A screaming comes across the sky – old phone numbers. I try to decide whether I prefer chunky peanut butter over creamy. Chunky, I conclude. Commercial jingles, yearbook quotes, I got the horse right here the name is Paul Revere, math equations, crossword-puzzle clues, Hotel-Motel Holiday Inn, anything, everything, a deluge of internal prattle.

This doesn’t bother me. Before coming, we had been instructed to discard any mantras we might have used in the past – not a problem, as I’ve always been mantra-free – but I actually have brought with me something of one. Really more of a slogan. It is this: “waterfall, river, lake.” I find myself repeating it, frequently, as I try to meditate. “Waterfall, river, lake. Waterfall, river, lake.”

The phrase comes from an article on meditation a friend had mailed me. It said that in the process of achieving an essential element of successful meditation, stilling one’s mind, it is inevitable there will first be a wild flow of random thoughts – a waterfall – which will gradually ease – a river – and then finally cease – a lake. I liked this notion, and I made a plan for myself: three days of waterfall, three days of river, three days of lake. If I made it that far, the 10th day could be whatever it wanted. So this first day’s waterfall feels fine, all part of my plan.

Unplanned is the continued torment of my lower back. I spot Wade, a few pillows in front of me. Wade from Minnesota. The man with the camp chair. It’s one of those simple seats, just two cushions that form a right angle. He’s sitting on one cushion and provided back support by the other. Glorious back support. Now I understand. But there’s nothing I can do. An hour passes. It’s impossible not to stare at my watch.

After 90 minutes, the sound of chanting emerges from speakers hung across campus. It’s Goenka. He’s singing, I think, in Pali. No one in my pagoda moves. The chanting continues for half an hour, and then everyone stands. The session is over. I’ve survived.

—

Dawn is just breaking, a crease of orange over the treeless mountains. It’s immensely lovely, and I get all goose-bumpy – I’m proud of myself; I’m joyous. I meditated for two hours. It’ll only get better, I know it. I’m going to thrive.

I stand in line for breakfast. A Dharma Server hands me an aluminum plate and spoon, and I serve myself a few scoops of oatmeal from a vat the size of a kiddie pool. I pour a cup of milk tea. I sit in a white plastic chair at a long crowded table and stare at my plate, avoiding eye contact, suppressing all social instincts. It’s very uncomfortable. Then I head back to my room and toss a bucket of water over my head – there are no showers at Dhamma Giri – and return to the little pagoda.

This time the teachers are in the room with us. Yogesh flips on the CD player, and I wait expectantly for Goenka to switch from Hindi to English. When he does, it’s the same thing: Concentrate on your nostrils. Nothing more. I’m in pain, and I’m restless, and I think about quitting. I do. It’s just past eight in the morning of the first full day.

I try to relax and focus on my nose, but the waterfall continues. I think about home, where it’s getting-the-kids-ready-for-bed hour, and I envision the whole process, the bath and the splashing, the argument over which video to watch – no, it’s not a SpongeBob night – the brushing of teeth, the reading of books – Harold and the Purple Crayon, something about mermaids – the complaints about needing to pee, the Band-Aids pasted over hidden owies, a round of ”Twinkle Twinkle.” And in this way an hour passes. Then Yogesh speaks into the microphone and tells us to take a five-minute break and return to the pagoda for a two-hour session.

From the 4 am wake-up to the 9:30 pm lights-out – that’s 17½ hours – we are expected, with a few rests and meal breaks, to meditate. Ideally, without moving. Of course without talking. Though there are, actually, two chances to speak. Either just after lunch or right before bed, you are permitted to ask your teacher a question. I show up at the very first opportunity, wait on my pillow, and when a Dharma Server indicates it’s my turn, I walk to the front of the pagoda and sit before Yogesh. He’s in his mid-sixties, I’d guess, with gentle brown eyes and long thin fingers and an air about him of utter kindness.

“My body,” I tell him, “is failing me.” I mention my back and knees and hips. Then I ask about the chairs. Five or six times during the course of the morning’s meditations, a Dharma Server had walked to a storage area behind the main room of the pagoda and returned carrying a rudimentary chair. He’d set it up in the rear, and a student would sit in it, leaning back, supported. Wade had his camp chair. I was in severe pain, so bad I couldn’t even attempt to meditate.

“May I have a chair?” I ask.

Yogesh gazes at me. So kind. “Do you have a physical ailment?” he asks. “A medical need?”

I pause. Here is my chance to make it easier on myself. I might have emptied my bank account for a chair. But I’ve sworn not to lie. Vipassana has a 2,500-year history of success. I should either play by the rules, I realize, or I should leave.

“No,” I say.

Yogesh tells me that my body is rebelling against this new challenge. It happens, he says. It’s an integral part of the process. I must work through it.

And with that, he returns me to Cushion 51.

—

For three and three-quarter days, our assignment remains the same: Think about your nose. The purpose, we’re told, is to hone our powers of perception until every microsensation is felt, every prickle of sweat, every wisp of air, every tingle and tickle and quiver and itch.

It works. My senses, all of them, grow incredibly sharp. When I step on a twig, it sounds like a firecracker. A sneeze is nearly deafening. I sit, during a break, in front of a bush, and I note that every leaf is a slightly different shade of green. I watch a leaf-cutter ant at work, and I move a little closer, and it’s true – I can actually hear it gnawing.

This, however, is also true: Pondering your schnoz is insanely dull. I’m not even sure how I get through it. Minute by minute, one session after another. My back does not get better. I am stuck at waterfall with no sign of impending river. Every time I pass a “Be Happy!” sign, I have to stop myself from ripping it down.

Then, late in the afternoon of the fourth day, Yogesh makes an announcement: We have finished contemplating the mysteries of our nasal passages. We are ready to learn advanced Vipassana. Even by this point, I have little idea what Yogesh means. My friends who’d gone previously told me it was better not to know much in advance, to allow things to unfold naturally, to be free from expectations.

We listen to a long recording from Goenka. Vipassana meditation, in essence, is like taking what we’d learned about the area around our nose – that there are continual sensations, some subtle, some blatant – and applying it to our entire body. Starting with our head and traveling to our toes, we’re to mentally pass over every inch of our body, detecting these sensations at each spot. We must not react – don’t be pleased by a transcendent tingle or feel ruffled by an off-putting itch – but instead remain steadfastly equanimous, secure in the knowledge that all sensations are temporary, that everything will change.

I confess that I’m a little disappointed. That’s it? I had hoped for something more, I don’t know, explosive. But I see the students who’ve been here before; I watch them meditate – stock still, an astonishing blissfulness about them. I think about Yogesh, ever serene, ever peaceful. My moods, in general, tend to swing widely – extreme joy when things go well, acute distress when they don’t. Goenka says it’s an unhealthy way to live. It’s essential, he teaches, to remain poised under all circumstances. Just be aware, keep balanced. I resolve to give it a try.

There are moments, brief and rare, when I succeed, when I’m on my cushion, and up and down my body I perceive myriad sensations, a full-body tingle. I’ve dissolved like an Alka-Seltzer tablet into the soup of the universe, a state Goenka calls “free flow.” It’s wonderful, though Goenka also warns us not to crave this feeling. Always, he says, be satisfied with what’s happening right now.

I find this difficult. Mostly because what’s happening is that I’m miserable. The day we’re introduced to Vipassana, we are also assigned individual meditation cells – some in the grand wedding-cake pagoda; others, mine included, in a large but less grand pagoda. Rather than always meditating as a group, we’re now expected to spend seven hours a day alone in a tiny, narrow room with a tiled floor and white plaster walls and a dim light. At least here, without teachers monitoring our posture, I can stretch out, head against the door, feet touching the far wall, easing the pain in my back. I feel as though I’m lying in my own grave. But even without the pain, I simply cannot meditate successfully for more than a few minutes. My head is still too noisy; my flow isn’t free.

Every group session begins with the same words from Goenka: “Start with a calm and clear mind.” Then he goes on to give further advice. But I can’t even get to step one. Everyone else in the room, it seems to me, is floating gleefully on a crystalline lake. I realize I can quit; I’m not being held here against my will. But there’s a part of me that believes a breakthrough is imminent. I’m a bull-headed man. I know how to endure. I once ran 100 miles in a single day (in 23 hours and 48 minutes, to be precise). I’m absurdly competitive – I can even turn something as airy-fairy as a meditation course into a kind of sporting event. And if all these other people are still here, no way am I leaving. This isn’t dangerous. I’m not climbing some 8,000-meter peak or crawling through a war zone. All I have to do is sit. Simplest thing in the world. So I soldier on.

But something happens to me. Something bad. It might be bearable to suppress my natural extroversion – to shut me up completely. Or you can corral my need to run or bike or swim or climb – to immobilize me completely. But the combination of the two is deadly. I have actually climbed an 8,000-meter peak; I have crawled through war zones. And let me tell you: Both of those are way easier than Vipassana. This coddled and calm environment generates in me a frightening rage. I begin to hate my fellow students. I hate the teachers. I hate the Dharma Servers. I hate Goenka. I hate the food and my bed and my cushion and my cell. I hate Vipassana. I hate myself.

I feel bored and angry and trapped and claustrophobic. Lonely, too, far lonelier than if I’d actually been alone. My brain seems like a centrifuge, continuously spinning. As the days pass, I feel less calm. The waterfall only intensifies. By the time the gong pounds to start the fifth day, there’s a Niagara busying in my head.

And then, sitting down for the predawn session, I make eye contact with the man on the cushion next to me. The portly one. There are protocols about what to do when this sort of thing happens. You should immediately look away. But instead – it’s an involuntary action – I nod my head in greeting. I break one of the rules. And my cushion-neighbor, startlingly, smiles back. Yes. A genuine human interaction. It lasts maybe three seconds but fills me with an unaccountable euphoria. Later that morning, we do it again. It feels lifesaving.

Then, on the zombie shuffle to lunch, I spot a rusty key on the path. I grab it. I’d developed a habit, over the days, of picking up random bits of junk – a scrap of string, a couple of screws, a safety pin, a paper clip. I don’t know why. All I do is pile them on my bed table. But in my room that evening, more crazed than ever by the lack of distractions, I fish the key out of my pocket. I grip it like a pencil. I take my Nalgene bottle. I make a scratch on the bottle’s side. Then another.

I spend half the night, headlamp on, in a fit of pent-up angst, scratching an entire letter, a cri de coeur, on the side of the bottle. Probably a thousand words long. It’s like one of those manifestos psycho-killers occasionally produce. Most of it, fortunately, is unintelligible, though what I can make out is deeply paranoid. I wonder if I’m being brainwashed, if the food is poisoned, if I’d really be allowed to quit.

During a group meditation the next day, I imagine I’m suffocating – I am suffocating! – and my legs begin to thrash about on my cushion, and I pinch my cheeks, fiercely, as if trying to wake myself from a nightmare, and sweat pours from me, and I can think only of hopping to my feet and sprinting away. Forget my belongings; just make an escape. When the meditation session ends, Yogesh makes eye contact with me and motions for me to come forward. As everyone else files out of the pagoda, I walk to him. I sit. I believe I’ve been so undisciplined that he’s going to kick me out of the center for disturbing the real meditators. I hope he’s going to kick me out.

He looks me directly in the eyes. “Michael,” he says. Softly, compassionately. Using my whole name – everyone calls me “Mike” – like my mother always did. “Michael, what’s wrong?”

I try to answer, but my mental scaffolding collapses. I break. Tears flow down my cheeks. Yogesh continues to look at me. And when I squeeze myself back together, he smiles.

“This is wonderful, Michael. Truly. So much is coming to the surface. This is powerful. I think you are getting more out of this course than anyone else.”

To my amazement, I feel better. Five minutes ago, I was planning to run off. Now I think that I am, indeed, receiving a greater benefit than any of those motionless meditators. I might even be winning the course.

—

The moon grows full and begins deflating. My aches start to fade. I’d like to say the meditation gets easier, but it doesn’t. Not a single minute feels like it has less than 60 seconds. I time myself on my wristwatch to see how long I can sit without moving. My record is 27 minutes. I keep up the illicit relationship with my neighbor – a wink, a grimace, a smirk, a sigh.

One night, also in defiance of the rules, I read the label on my deodorant. And my hand sanitizer. And my toothpaste. Then I break into my first-aid kit, looking for other things to read. I see the bottle of painkillers: prescription-strength hydrocodone. I can’t help myself – I swallow a few pills and zone out for a couple of pleasant hours.

A few times, when I’m supposed to be meditating in my cell, I wander about campus, avoiding the Dharma Servers – the Dharma Police, I rename them. I observe, in a nearby field, a group of boys playing a game of pickup cricket. I dance, by myself, to the faint licks of an unseen stereo. OK, I admit it – it’s more than a few times. I come across other truants; a couple of guys chatting, one man speaking on a cellphone. I watch the distant cliffs morph from tan to purple to black as the sun slides away.

I come up with a theory: People who are really good at meditation, who can truly suppress every thought, probably didn’t have many thoughts in the first place. They’re stupid. I like this theory. It makes me feel better. Who the hell wants to be a Buddha anyway? It’s not a bit of fun; there are no girls. I’d rather be Derek Jeter.

The final meditation is a one-hour group session. My head’s still a waterfall, strong as ever, so I envision the drive from my home in Montana to the entrance of Yellowstone National Park – a trip that takes almost exactly an hour – and I visualize every bit of scenery along the way. I picture myself filling up my car with gas, buying a Diet Dr Pepper, swerving to avoid a deer, stopping to snap a photo of a bighorn sheep.

When it’s over, our vow of silence is still in effect. We’re not permitted to speak until we’re past the grand pagoda. We walk along the paths, students from the other groups spilling out of their pagodas. I fall into stride with a young Indian man, and I sense both of us speeding up, aching to reach the finish line.

I tend to measure my travels not by what I see but by how intensely I feel. And on this scale, I realize in my last moments of silence, my time at Dhamma Giri qualifies as the most profound trip of my life. Even weeks later, long after I’ve resumed the rhythms of normal existence, I can see that the 10 days have altered me. The stream of petty, kid-centric stresses that used to keep me perpetually riled – the third glass of spilled apple juice; the cellphone dropped into the toilet – now seem precisely what they are: not that big a deal. And even when I’m faced with a couple of truly big deals, like a death in my family and an emergency-room visit with my son, I feel this calm and clear-headed understanding of the vicissitudes of life.

Goenka says that it’s essential to keep meditating, two hours per day. I don’t even bother trying. None of my friends has noted any diminishment in my capacity to chatter. But the truth is I actually do feel a little bit enlightened, more deeply connected to the world. I feel like I have a greater understanding, and acceptance, of who I am, my foibles and strengths.

I communicate with a few of the other students and discover that they, as well, struggled greatly. One guy admits that he also cried. Another, an Indian student, tells me that to pass the time, he gave almost everyone a nickname: I was “Steve Jobs” because I’m Caucasian and balding and wear circular glasses. Fifteen people, I learn, quit the course, most in the first couple of days.

But overall, I think of the three-word review I give to the young man I’m walking next to when we conclude our silence. It remains my most honest and unalloyed assessment. The instant I was able, I turn to him, and he turns to me. Both of us are grinning radiantly. And I speak my first words: “That fucking sucked.”

— end —