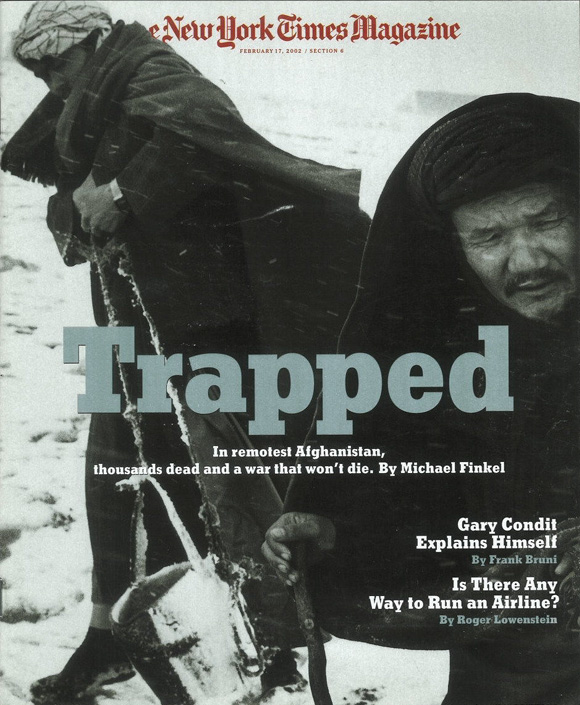

They had a radio, just a single battery-powered radio, so the news traveled by word of mouth up and down the footpaths of Abdulgan, village to village, until everyone knew. They knew what was happening elsewhere in Afghanistan. And therefore the people of Abdulgan not only suffered, they suffered with the knowledge that they were some of the last ones suffering. The news on the radio throughout the fall and early winter of 2001 was of Taliban retreats and food-relief plans and celebrations in cities released from oppression. Yet in the district of Abdulgan, where they had been tortured by the Taliban for years, people were still dying. Not just a few people, but hundreds, even thousands — a few thousand dead, and more dying.

The people of Abdulgan did not die all at once, and they did not die on television or in a manner that could be called spectacular. They died in prosaic ways — of disease and cold and starvation. They died because they were trapped by nature and politics and war. They died because they were caught in the cross-fire of Afghan history. They died deep in the mountains of northern Afghanistan, dozens of miles from the nearest dirt road. And they died because this war, like all wars, is a complicated and messy affair.

For those who didn’t die, for those still healthy as conditions appeared to be improving almost everywhere but in Abdulgan, a choice had to be made. People had to decide whether to believe the radio reports, which said that the remaining pockets of Taliban fighters would quickly be defeated. They had to decide whether to trust the governor of Abdulgan, who promised that relief agencies would send food their way. And if they doubted the radio reports or weren’t certain about their governor’s knowledge, and if they were still physically strong and mentally steely, then they had to decide — and decide quickly, before the snows eliminated any choice at all — whether they wanted to remain in Abdulgan and leave themselves to fate, or whether they wanted to try an escape.

—

Khuda Bakeh decided to escape. He felt that he and his family had waited long enough. Too long, maybe. In mid-October, when the American planes first flew over Abdulgan on their way to bombing runs in the northern cities, Bakeh thought he was witnessing his family’s salvation. ”We thought it was a gift from God,” he says, speaking in Dari, the Afghan dialect of Persian. ”We thought we would be freed, released from our situation. We all did.”

The planes flew directly over Bakeh’s head — the little buzzy F-14’s and F-18’s from the aircraft carriers, then later the B-52’s with their horizon-to-horizon contrails. Every day for 15 days, fighter planes flew over Abdulgan. Bakeh waited for them to drop the yellow food packets that he’d heard about from the radio reports, but the food never fell. One day the planes stopped. Before long his own food supplies were dangerously low.

He waited as disturbing news reached his village. The news came in typical Abdulgan fashion — relayed along the web of footpaths that link the 55 or so villages in the district of Abdulgan, high up in the mountains, with the more fertile districts in the valleys far below. The disturbing news came not from those who had been listening to the radio but from people who had recently made the trek up from the valleys. The American bombing, they said, had sparked a mass Taliban retreat, which had brought the Taliban into the mountains near Abdulgan. This was an unintended consequence of the American action, but devastating nonetheless.

Rather than fewer Taliban troops patrolling the foothills, there were now so many soldiers that the Taliban had nearly surrounded the entire region, blocking all the traditional footpaths to Abdulgan. It was nearly impossible for supplies to get up the mountains and extremely dangerous for anyone to come down. So Bakeh and his family waited. They waited as the month of October expired and November began. They waited as the wind carried a chill with it, indicating that winter was on the way. They waited as friends and relatives and neighbors fell ill, and they wondered how long their own health would endure.

In truth, if he really thought about it, Bakeh had been waiting for years. The residents of Abdulgan are Hazara, and they had been suffering since the Taliban finished capturing most of northern Afghanistan by summer 1997. The Hazara, the third-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, after the Pashtuns and the Tajiks, live primarily in the mountains of central and northern Afghanistan, a region they call the Hazarajat — the land of the Hazara.

Unlike nearly every other ethnic group in Afghanistan, the Hazara are followers of the Shia sect of Islam. They do not accept the legitimacy of Islam’s three earliest caliphs, or spiritual leaders. The Taliban, who are Sunni Muslims, regard the Hazara as infidels and have done everything in their power to destroy them.

Only the rugged terrain, which had protected the Hazara for centuries, prevented Taliban troops from launching an all-out ground assault. Instead, the Taliban planted land mines throughout the Hazarajat and sent their small air force on bombing runs over Abdulgan. They tried to stop all supplies from reaching the Hazara’s mountaintop settlements and to block all Hazara farm goods from reaching the markets down in the valley. If the Hazara, even civilians, were caught trying to descend from their villages, they often faced imprisonment and, sometimes, execution.

The Hazara tend to be short and stout and rather Mongol in appearance; they are, by anthropologists’ best estimates, descendants of the Mongol invaders of the 13th century. They do not look like the other peoples of Afghanistan; many do not grow facial hair particularly well. On this basis, above and beyond religious beliefs, they were vulnerable to being persecuted by the Taliban.

At the same time that the Taliban were tormenting the Hazara, northern Afghanistan was struck by drought. Many Hazara do not find this a coincidence. ”It was as if God was angry at us,” Bakeh says, ”but we did not know what we had done.” Beginning in 1998, there was simply no more rain. Bakeh is a wheat farmer, and the drought destroyed his fields. His family had no source of income; they couldn’t harvest enough wheat even to make their own bread. Almost nothing was growing in Abdulgan, and only a tiny quantity of goods made it through the Taliban blockades. Those goods were now extremely expensive. Soon there was no water in Abdulgan’s wells. Food was scarce; what little water was available was dirty and brackish. Disease began spreading — first a districtwide outbreak of malaria, then cholera, then measles, then tuberculosis. People were dying.

During the spring and summer of 2001, many families elected to abandon their homes and try to make their way to refugee camps. ”We all thought about it,” Bakeh says. ”Everyone did.” But it was always dangerous to go. There were reports that Taliban troops were torturing civilians, sometimes killing them like cattle, hanging them by their feet before slitting their throats. This is why Bakeh decided to wait. He had a wife and five young children, and he did not want to put his family in danger.

At the time of the terrorist attacks in the United States, Bakeh and his family still had a little to eat. But soon, in order to pay for food, Bakeh was forced to sell his possessions. He sold his donkey to a merchant who had come up from the valley. He was paid about $80, the equivalent of several months’ earnings. This helped for a while. But without a donkey, the family could not haul water; because of the drought, the nearest source of water was now an eight-hour hike away. The family had to buy water. Five liters of muddy water was selling in Abdulgan for $3. The money from the donkey soon ran out, so Bakeh sold his goats and then his chickens. He sold his two cows and his new wooden plow. He knew this meant that even if the drought ended, he would not be able to till his fields; the future was something he no longer planned for. He sold his carpets and his teapot. His family sold everything they could sell to merchants in the valleys, and still they had very little food.

And then, because they live in a place where the nearest trees are miles away and because they had sold their donkey, there was no way for Bakeh’s family to collect firewood. They would have to burn twigs and wheat stubble. Winter was approaching. Snow had already fallen. The American planes had flown over with bombs but not with food. To people in Abdulgan, the Taliban forces seemed stronger than ever. Panic was setting in.

Nearly every household in Abdulgan was in the same situation as Bakeh’s family. In fact, Bakeh’s family was comparatively fortunate. ”Children in other homes would complain of stomach cramps,” Bakeh says. ”And then they would be dead by that night. It happened to many, many children. It got so that when a child would clutch his stomach and say, ‘I have pain, I have pain,’ we would all cry and say goodbye to that child, because we knew he would be dead.”

By this point, in early November, Bakeh realized that it was only a matter of time before his own children — who ranged from a 7-month-old son to a 12-year-old daughter — would come down with stomach cramps. Bakeh was 34. His wife, Gulnegar, was 31. ”We felt we could not just sit and die,” Bakeh says. ”We were, by the grace of God, still healthy. We had to take a chance.” And so he made the decision to leave. ”It was,” he says, ”the hardest decision of my life.”

—

Leaving Abdulgan, even under the best of conditions, is never easy. Abdulgan is possibly the most remote district in all of Afghanistan. It is located about 150 miles south of the city of Mazar-i-Sharif, high in the Mushkel-Hal Mountains, which roughly translates from the Dari as the Hard Walking Mountains. The district encompasses several hundred square miles, though how many exactly is hard to say, as the land is so rent and riven. It takes days to walk from one end to the other. Each of the 55 villages within Abdulgan is perched upon its own mountain — 55 villages atop 55 mountains. It is actually quite beautiful, the type of backdrop better suited for a fairy tale. When you are in Abdulgan, it can seem as if it is the only place in the world, and when you are anywhere else in the world, it can seem impossible that Abdulgan exists. On maps of Afghanistan, the district does not appear to be there; where its name should be printed, maps show nothing but uninhabited wilderness.

Bakeh’s family was not the only one to abandon Abdulgan. Thirty-nine neighboring families joined them — a total of about 200 people. They were some of the strongest in Abdulgan. They decided, for safety, to travel together.

Their plan was audacious. They knew that they could not descend the mountains following traditional paths — with the presence of the Taliban, they felt, this was akin to suicide. Instead, they were going to journey through the vast, craggy wilds of central Afghanistan, a land of seemingly endless mountains, a realm that looks, from high points, like a still life of roiling seas. They would leave by the back door, through terrain so rough the Taliban would never be there; no humans at all, they expected, would be there. They’d be completely on their own.

Such a route would not take them near any refugee camps. Instead, their plan was to walk nearly 400 miles to the west, all the way to the border of Iran. Most Hazara feel a strong affinity with Iran, primarily because Iran is home to the largest Shiite Muslim population in the world. The families who left Abdulgan believed that if they were able to make it to the Iranian border, they would appeal to their fellow Shiite Muslims and, given their desperate circumstances, be allowed to cross into Iran.

Early on the morning of Nov. 8, 2001, Bakeh and his wife and five children and the other 39 families began to walk. It was the first time any of Bakeh’s children had left Abdulgan. They walked down the far side of the mountains, into the wilderness, toward Iran. They turned their backs on their village, their people, their country. They were giving up on Afghanistan. They were escaping.

—

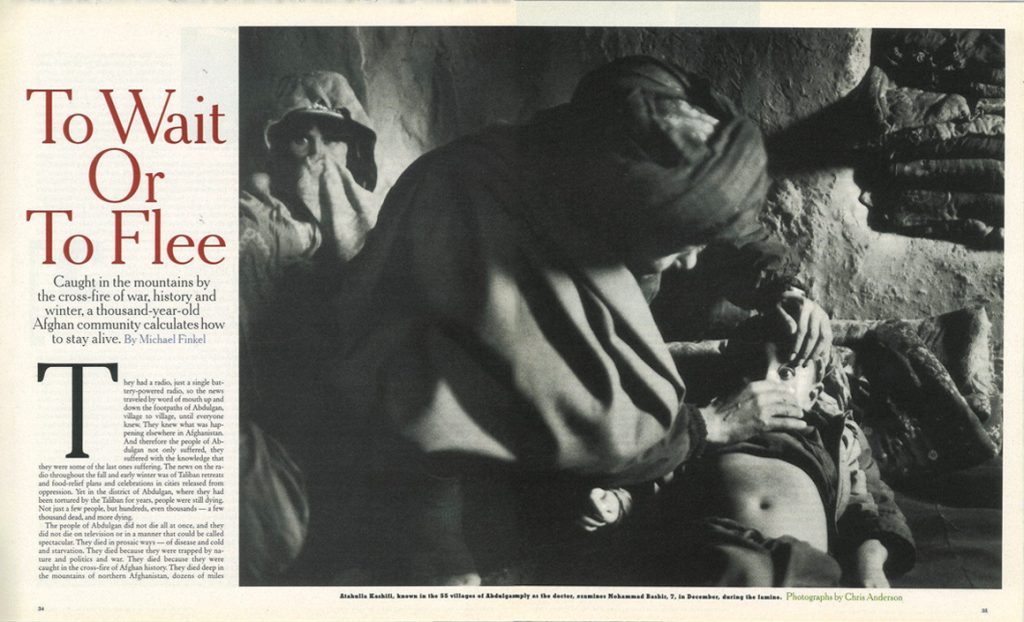

The owner of Abdulgan’s only radio is a man named Atahulla Kashifi. Most people who know him, though, refer to him simply as the doctor. The fact that he is not really a doctor is of little significance; he is more of a doctor than anyone else in Abdulgan. In 1979, when he was a soldier in the government army, Kashifi worked as a nurse for eight months in the military hospital of Kabul. Later, he read two textbooks, which he keeps in his house: ”Drug Treatment and Complications” and ”Medical Information for All.” These are his full medical qualifications. Kashifi is also Abdulgan’s governor, military commander and — by virtue of owning the radio — the primary source of news from the outside world.

Kashifi lives in the center of Abdulgan, in a mud-walled fortress he built for himself and his family in the district’s largest village, a place called Bini Gaw. In Dari, bini means ”head” and gaw means ”cow,” though even the doctor, who was born here, cannot explain why his village is called Cow’s Head. There is no electricity or plumbing in Bini Gaw or anywhere else in Abdulgan. Nor is there a school, a bakery, a butcher shop or even the most meager of stores. The only communal building is a mosque.

Before the Taliban took control of northwestern Afghanistan, about 3,000 families, by the doctor’s tally, lived in Abdulgan. Three thousand families means at least 15,000 people. From the time that the Taliban came to power until the United States entered the war, the doctor estimates that the district lost about half its population — more than 7,000 people. ”Some of them escaped to refugee camps,” he says. ”Some were killed in the fighting. But many of them died right here.”

Prior to the American bombing, the doctor could still conduct a modest amount of trade with the merchants who were willing to travel the paths between the valleys and the mountains. He was able to procure a few needed medicines. He felt, as Abdulgan’s one-man hospital, that he was solely responsible for the health of everyone in the district.

To purchase medicines, he sold his most treasured possessions: his horses. ”Before the Taliban were here,” he says, ”I used my horses to ride into the valleys. I rode them to other districts, to faraway villages. When I sold my horses, it was like saying to the people: ‘I am staying here. I am staying with you. I am staying until the end of this terrible time.”’

When the American planes flew overhead, the doctor, like everyone else in Abdulgan, was joyous. After the bombings, though, it was nearly impossible to obtain medicines. The doctor feared that he was unable to provide even the most basic help. It wasn’t long before he felt the first twinges of despair. ”I saw too much suffering,” he says. ”It made me an old man.” He was 45, which is just about the life expectancy of a person living in Afghanistan. The doctor was, in fact, an old man.

As if to confirm this, his health began to falter. He suffered, almost daily, from severe headaches — some so bad he had to lie down until they passed. To combat the headaches, he began chewing a substance called naswar, a powdery bright-green tobacco and herb mix, intensely strong, that numbs the entire body. He’d purchased a large supply of naswar over the summer, in part to dispense as a medicine. He began it chew it every day, all day, keeping himself perpetually numbed.

The doctor, of course, listened to the reports on his radio about the imminent demise of the Taliban, and he heard the conflicting information emerging from the valleys about the increasing potency of the Taliban. But unlike most people in Abdulgan, he realized what was happening. Kashifi had been a soldier for 22 years. He had lived through two decades of continual fighting. He understood how war worked.

He knew that American planes were first bombing Taliban positions near major cities. This made sense: the cities had to be liberated before the countryside. He knew, too, that the Taliban had retreated into the foothills below Abdulgan. He realized that it had to be this way — the bombing, he thought, was good for the country as a whole, no matter how unfortunate it was, at least in the short term, for the people of Abdulgan.

What panicked the doctor, though, what made his head throb and his desire for naswar intensify, what made him grab at his yellow strand of prayer beads and run his thumb over them as fast as he could — two beads at a time, like a man in need of miracles — was a simple question that he was unable to answer: how long would the short term last? For he knew that this was a race against time.

”People were getting sick; people were dying,” the doctor says. ”I knew this would stop only when help came — or when there was nobody left to die.”

Kashifi calculated that the bombing raids would move from the cities to the countryside and that the Taliban would indeed be defeated. Then he figured that relief agencies would follow the same course as the bombs — the cities first and then the countryside. So, in late October, he made an announcement and sent word of it to the 55 corners of Abdulgan. The situation, he announced, was going to get better. He said that it would be best to remain in Abdulgan rather than to try to leave. And then he made a promise, one that he later wished he hadn’t made. He promised the people of Abdulgan that they would soon receive help.

Days after the doctor’s announcement, when news circulated through the villages that 40 families were planning to leave, there was tension in Abdulgan. The doctor says he felt it. Some people thought that by leaving Abdulgan, the 40 families were essentially surrendering their homeland to the Taliban. Others wished that they were healthy enough, or brave enough, to go along.

The doctor did not try to stop them. He knew that his promise was not really a promise. It was more of a guess, a prayer phrased as a promise. He thought that Bakeh and the others had made a bad decision, but he could not know for sure. It was conceivable that Bakeh’s choice to leave was the right one. Which meant it was possible that Kashifi’s announcement had actually further imperiled the lives of everyone who was still healthy in Abdulgan.

But Kashifi could not abandon his village. As governor of Abdulgan, he felt rooted in the place, but it was more than that. Abdulgan, he says, is part of his genetic code. One of the doctor’s favorite pastimes is to count the names of his ancestors. He does it in a singsongy style, as if reciting a lyric poem: ”My father’s name was Qamberali. His father’s name was Haiderqul. His father was Boi Mohammed. His father was Jafar Big. His father was Masum Big.” He can go on for some while. ”My family,” he says, ”has lived in Abdulgan for a thousand years.” And so he decided to stay and minister to his people.

—

The 40 families walked out of Abdulgan and into the wilderness. Bakeh walked with his wife, Gulnegar, who carried their infant son, Ali. Their four daughters — Rabia, Razia, Samana and Chamangul — walked alongside them. They had only a tiny amount of food. They had no tent. There were 10 blankets to share among 200 people.

They were wholly dependent on the offerings of nature and the fickle moods of the skies. They drank water out of mountain streams; they foraged for roots and wild berries in the lowlands. They ate nothing when they were in snow-covered areas. They inched up mountain faces, worked their way around cliffs and exhausted themselves climbing in and out of canyons. ”It was harder than any of us had imagined,” Bakeh says. At night, they all slept together, on the ground, under the stars. ”We slept in one big pile,” Bakeh says, ”like dogs.” During the night, the people on the outer edges of the sleeping pile rotated inward, and the people in the middle were spun outward. In this way, no one froze to death.

Even the youngest children had to walk — the group had no donkeys. They had no warm clothes. Some had plastic shoes; some only had open-toed sandals. The drought had ended, and they walked through snow and ice and freezing rain. They walked through some of the most challenging terrain on earth. They walked for 20 days and slept outside for 20 nights. And then, at last, without suffering a single fatality, they arrived at the Iranian border.

—

As the 40 families walked, so, too, did the doctor. He had decided that he would travel the footpaths of Abdulgan and tend to the ill until his promise of relief was fulfilled. During the three weeks it took for Bakeh and the others to reach the Iranian border, there was no sign that any aid was coming to Abdulgan. The situation grew worse. The doctor walked as far as he could. Sometimes he walked all day to reach a distant village. Often, when he grew weak and tired, he wished he were riding one of his horses, but such thoughts, he says, made him even more weary, and so he tried not to think about his horses.

There seemed to be a different epidemic in every village. Some of the sicknesses the doctor could not identify — sicknesses with strange and alarming symptoms. In Dasht-Kodogh, people’s eyes teared as if they could not stop crying, and then they went blind. In Folad, people’s teeth turned brown and rotted away. In Bunawash, it was hair that fell out, and scalps became covered with sores.

Starvation was no longer a threat — it was a daily reality. Every week, through the month of November and into December, Kashifi says that more than a hundred people in Abdulgan died of malnutrition. The precise number is hard to know, but just in Bini Gaw, the doctor’s village, there were at least two deaths every day.

On some of his walks, the doctor would pass a home he’d visited a week or two before, and it would seem unnaturally silent, and he would look to the stovepipe and that, too, would be still. He’d walk inside and no one would be there. And then he’d ask the neighbors, and they would confirm his worst fears: the whole family was dead. Dead and buried, up on a ridge, in graves that bulged from the frozen earth, marked with a single unadorned stone.

In Boya Boya, in the most remote corner of Abdulgan, the doctor was told of an elderly woman whose husband had died of hunger. By Islamic custom, respect must be shown to the dead by burying them as quickly as possible. The ground was frozen, though, and the woman was unable to dig a grave. Her neighbors were too weak to help her. So she buried her husband in the only patch of soft dirt she could find. She buried him inside their home. A few days later, the doctor was told, she became convinced that her husband’s spirit was angry. The spirit demanded a proper burial place. The woman realized that she could not live on top of her husband’s grave and fled her home. She did not make it far. Her frozen body was found the next morning.

At many places, the doctor saw what he called ”skeleton people” — people who were alive but who were not really alive.” Meanwhile, his own health deteriorated. His headaches seemed ceaseless. He chewed and spit out so much naswar that a trail of green stains marked his daily journey through the snow.

His health problems troubled him. He was used to being robust, energetic. And indeed the doctor was, for the most part, an imposing-looking man, with a wide, sun-wrinkled face, a broad chest and thick fingers — and yet with ankles and calves so thin that he often gave the impression, while standing, of being precariously balanced.

By mid-December, when Bakeh and the families had been gone for nearly six weeks, the snow became almost too deep for the doctor to travel through. The wind seemed never to quit. He felt weaker and weaker, so he began limiting his walks solely to the paths around Bini Gaw. The village is made up of about 200 houses spread over a large flat-topped mountain, with outlying communities on smaller peaks all around. The terrain is barren and severe, treeless save for six spindly aspens, which are fenced off as if in a museum.

Kashifi tried to visit at least two dozen families a day. These walks were never easy. He carried what few supplies he had left — vitamin C tablets, protein syrup, rehydration salts, rubbing alcohol, a ledger book and a stethoscope. He wore black plastic shoes and a brown turban and a navy blue jacket. He tucked his pants into his socks. He hid his head within the folds of his large brown shawl, prodded at the path with a thin hiking stick and pushed his way through the snow.

The houses in Abdulgan are little mud-and-straw boxes, with thick walls and tiny mouse-hole-shaped windows covered with cellophane. Inside most homes is a cylindrical steel stove, about the size of an oil drum, with a door at the bottom for feeding in wood and a section on top, with a spout, in which to boil water for tea. The poorer families have only a fire pit, and their walls were usually black with soot.

The doctor would knock, twice, then duck under the low doorway and stand in the entrance for a moment, blinking as his eyes adjusted to the smoke and the dark, until gradually there were shapes, and the shapes became humans. He would take in the scene and do what he could to help. He checked on the ailing and the elderly and the weak. He checked on the children. He saw people he had pulled from the womb die of starvation and sickness.

He visited his friend Abdul Razik, who had stepped on a land mine in the foothills below Abdulgan and was missing most of his toes, eight of his fingers and both of his eyes. He spent some time with Mohammed Ghula, who was shot by the Taliban at close range and had a gap in his face where his lower jaw used to be.

He looked after Rahela Ayob, whose husband, daughter and son all died of malnutrition — he tended to her as best he could while she squatted in the corner of her unheated home, mute, unkempt, rocking back and forth on her ankles, clutching herself with her arms, waiting to die. In front of her house, on her laundry line, was a string of frozen clothes. It was as if she’d given up on life, midwash.

Starvation, he saw, can be an unpredictable killer. In another home, a grandmother and grandfather — Merza and Sakena — tended to their 4-year-old grandson, Ahmed Ali. For some reason, the elderly and the infant were alive, while Ahmed’s parents were dead.

He stopped by the home of Safder Abas and his 11-year-old daughter, Razia. Abas owned one of the only Korans in Bini Gaw. It was well worn but beautiful, nearly the size of a tabloid newspaper, with a red silk cover. Abas, though, could no longer read it — he was blind and near death, too weak even to sit up. Razia was evidently something of an artist; she had taken a bit of charcoal from the stove and had decorated the walls of her home with drawings of trees and flowers and chickens and two people riding horses into a sunset.

One thing the doctor did, at the end of every visit, was enter the name of the family in his ledger book, with the services rendered and the fee owed. There was not one family in all of Abdulgan with extra money, but still the doctor made entries. In his home, Kashifi had a second ledger that was completely filled up — a chronicle of thousands of unsettled balances. He did not actually expect to be paid, but it was part of his routine, and even when things were at their worst in Abdulgan, he did not want to change it. His patients knew that he made entries, and he felt that if he stopped, they might think he’d given up on them. So he continued with his ledger.

Once Kashifi stopped walking beyond Bini Gaw, people sometimes walked to him. Three mothers made a six-hour hike from Bandak village, each carrying a sick child. The children had fevers, spots on their faces and bloody diarrhea. ”I did not know what to do,” the doctor says. ”I had nothing to give them. I let them lie in my house, but by the time the sun came up, all the children were dead. The mothers had to walk back alone.”

When things like this happened, it made the doctor angry. He was upset that there was not a better doctor in Abdulgan. ”I am a doctor,” he admits, ”who is not really a doctor.”

He saw a hundred different types of suffering. Most families suffered silently. They sat in their homes, around their stoves, and said nothing. Those who were too weak to sit lay down. Some families hardly spoke a word all day. Some scarcely moved. There was only the hiss of the fire and the drip of snowmelt coming through the roof. At times, the doctor walked down a path, house after house, and heard not a single human voice. The houses were so silent it frightened him. Abdulgan, he says, used to sound like a riot of children. Now even the babies didn’t seem to cry.

But not all families were quiet. Some starved angrily, some aggressively, some with wails that could be heard halfway across a village. Abdul Ahad, who was near death, lay with his 8-year-old daughter, Roqia, squatting next to him and cradling his head while Ahad moaned and yelled and wailed and shrieked. His eyes were light brown and cloudy. Most of his teeth had fallen out. He owned an aluminum trunk and a wool jacket, both of which he had refused to sell. Two teacups were on the floor, and three-quarters of a piece of bread.

On the wall, in a wooden frame, was a photograph of Ahad and his wife, Amena. It was taken more than 10 years before. Ahad had made one trip out of Abdulgan in his life, to Mazar-i-Sharif, a weeklong journey by donkey each way. He went with Amena. They had their photo taken. Now Amena was dead. His brother and his brother’s family had left Abdulgan months ago in an effort to reach a refugee camp; they hadn’t been heard from since. As Ahad wailed, his hands balled into fists, as if he wanted to strike someone. Snowflakes, taken by the wind, flashed by the windows of his house like shooting stars. He cried nonstop the entire time the doctor was there. His daughter never left his side.

Some families starved stoically, in almost unbearable circumstances. The four Hussain siblings — Ali, 15; Hashem, 10; Kazem, 9; and Salima, 8 — lived in the charred remains of their family’s home. A Taliban bomb, dropped from a plane, had landed on the home, killing both their parents and an infant girl. They huddled in the half of their home that was still standing. They did not have a fire, though neighbors had brought over some hot tea and a few blankets. Salima, the only girl, had huge brown eyes and an emerald green shawl. She shivered uncontrollably. A wicker bird cage sat near the entrance of the home, but there was nothing in it.

On these walks, Kashifi says, he felt an incredible range of emotions — sometimes bitter, sometimes defeated, sometimes oddly hopeful. Sometimes, he says, he felt nothing at all. In front of his patients, he never appeared anything less than calm. ”I try to keep all of my feelings inside,” he says. He hardly slept. He spent little time with his wife and six children. He seemed to subsist solely on tea and naswar. At night, he often stood outside in the cold and wondered why all of this was happening. The doctor did not blame God. ”I never became angry with God,” he says. ”I became angry with humans.”

One family that inspired the doctor was Sayid Mossa’s. There were five in the family — Mossa and his wife, Massoma; his mother, Mariun; his 11-year-old son, Mahdi; and his 3-year-old son, Murtza. There was also a cat. On the day the doctor visited, everyone was sitting around the stove. Because they had no firewood, they were forced to burn hay — hay that was originally supposed to feed the family’s donkey, which they had sold to buy food. The hay burned quickly; the room was cold.

When the doctor entered their home, Mossa pushed himself to his feet and nodded a greeting. The rest of his family did the same. They had decided, as a family, that there was no reason to toss aside tradition, to ignore decency, to trample politeness. This was all they had left. So when a respected elder entered their home, they stood up. They were not aware that in many other homes, people had stopped standing, even for the doctor.

Mossa kept his blue turban wrapped crisply about his head. His children wore fez-shaped hats, colorful as bouquets, and sequined vests. His wife and his mother were wearing flowered dresses and flowered head scarves. The family’s sleeping mats were folded and stacked in a cubby cut into the wall. Shoes were lined up at the door. The floor was swept. Elsewhere in the village, in other homes, some people had lost interest in grooming or cleaning or dressing. A few men had stopped tying their turbans.

Kashifi examined the two children. He pressed on their chests and checked their eyes and looked into their ears. The children were sick — they had headaches, stomach pains and diarrhea. ”Malnutrition,” Kashifi said. He said it dozens of times a day, in every house. He asked if the family had anything to eat. Mossa pointed to a bowl on the floor. Inside the bowl was a lump of greenish-brown paste; it was made of flour mixed with grass and water. Yesterday, Mossa said, the family had dug through the snow and found the grass.

They had a little more grass and a small quantity of flour, which was kept wrapped in a swatch of burlap. The family, Mossa said, had decided that they would not eat their cat. The cat was their pet, though it didn’t have a name. Or, rather, it did. ”The cat,” Mossa said, ”is named Cat.” He smiled when he said this. He was starving and he was making a little joke. The elder son, Mahdi, rubbed the cat. The cat nudged against him. Mahdi reached into the bowl with the flour and the grass and scooped out a bit of the paste and put it in front of the cat, and the cat gobbled it up.

—

At the border of Iran, the 40 families met a group of men who were willing to smuggle them across and bring them to a place where other Afghans were living. All the men wanted was money. The families, of course, did not have any money, none at all. They begged the men to take them across anyway. They begged them to do it out of compassion, out of religious duty. ”We told them that we were Shia,” Bakeh says. ”We pleaded with them.”

But illegal border crossings are generally not situations in which there is a surplus of humanity. The men wanted money, and without money they refused to even consider aiding the families. ”They told us,” Bakeh says, ”We are not running a charity.’ They said, ‘If we are caught helping you, we will pay with our lives.’ They didn’t care if we died right there. They said that if we tried to cross without their help, they would have us arrested.”

The group turned back. They had nowhere else to go. ”It was the worst moment of my life,” Bakeh says. They started walking back toward Abdulgan. By this time, though, the snows had drifted deeper. No one had much energy left. Gulnegar, Bakeh’s wife, became ill. She had severe stomach cramps; she coughed up blood. The next day, she could no longer hold Ali, her infant son. She could hardly walk. Bakeh took the infant and begged his wife to try and stay with the group — if they fell behind, they would surely die. But Gulnegar was unable to go on. On the fourth night of their return trip, she died. Bakeh used up much of his own remaining strength to bury her.

He continued on with Ali and his four daughters. But without breast milk, Ali also became ill. There was nothing Bakeh could do. Ali, his only son, also died. He stumbled on, grief-stricken. ”I would have laid down and died if it wasn’t for my daughters,” he said. On the trip back to Abdulgan, five more people died.

But, of course, even those who made it back were far from safe. They were exhausted, hungry and trapped, and once again in Abdulgan. The day they returned happened to be Id al-Fitr, the biggest celebration of the Muslim year, the feast marking the end of the monthlong fast of Ramadan. They had nothing to eat. Bakeh’s four daughters sat in their house and wailed so loudly that they could be heard a valley away, where Kashifi was walking.

The doctor hurried to Bakeh’s house, but there wasn’t much he could do. It was mid-December. The people who had tried to leave had failed, and his promise of aid seemed to have been a false one. The evening the 40 families returned, the doctor had a dream. ”I dreamed,” he says, ”that everyone in Abdulgan had died. I was the only one left.”

After the dream, the doctor woke up and felt very disturbed. ”I had a thought that I’d never had in my entire life,” he says. ”I thought, I have begun to hate this place.”

Less than three weeks later, in early January, something of a miracle happened in Abdulgan: the doctor’s promise was fulfilled. The miracle began with a man named Hamidullah Hamidi, a 38-year-old professor of engineering at the University of Balkh, in Mazar-i-Sharif. During the Taliban occupation, the university had been closed, except for Koranic studies and a few other classes. Though the city had recently been captured by the Northern Alliance (with the help of the American bombing runs that the citizens of Abdulgan witnessed) and the university had reopened, there were no funds to pay professors. Hamidi needed a job.

He was hired by the International Rescue Committee, a worldwide relief agency specializing in refugee aid. Hamidi’s job was to seek out remote places in northern Afghanistan where people were in desperate need of help, spots that relief agencies may have overlooked. The assignment called for someone who was willing to explore mountainous terrain and endure no small amount of discomfort. The salary was $10 per day.

Hamidi was perfect for the position. He was familiar with discomfort. When the Taliban controlled Mazar-i-Sharif, Hamidi had been arrested and imprisoned for teaching classes in his home. While in custody, he was severely beaten about the head and nearly blinded. He now wears glasses so thick that his eyes, when you look at him, seem small and far away. The opportunity to help others who had been hurt by the Taliban was highly appealing, and he threw himself into the job.

He spent weeks in the Hazara homeland, traveling by foot and by donkey, up and over dozens of mountain passes, through ravines, above the tree line. Finally, he came upon Abdulgan. He was horrified. ”I could not imagine a more dire situation in all of Afghanistan,” he says. He met Kashifi and swore to return. He left his entire salary behind, so that the doctor might one day acquire more medicines.

The demand for relief goods in Afghanistan currently far outstrips supply, and it took a few weeks before Hamidi was able to organize a rescue mission — weeks that tortured him, he says, for he knew people were dying every day. Eventually, through a massive effort that included some 400 donkeys, several of whom froze to death during the journey, the International Relief Committee brought supplies of wheat to the people of Abdulgan. When the relief workers arrived, they found a scene of complete devastation, village after village filled with the dead and the dying.

Without conducting a survey of every family in Abdulgan, it is impossible to know exactly how many people have died since the start of the American bombing. The doctor says that in Bini Gaw alone, more than 300 people died during this time. In the nearby village of Bunawash, at least 50 people, according to Kashifi, are dead. In Shikar Darah, International Rescue Committee workers discovered that out of the 50 to 60 families who once lived there, only 3 survived — at least another 250 dead. These are just 3 villages out of 55. The total number of dead over the last few months has to run into the thousands.

In the far-off villages of Abdulgan, the snow was so deep that not even the donkeys could get through. In their desperation to obtain food, several young men from these villages tried to walk down toward the valleys so that they might carry some wheat back home. The journey was so difficult that four of these men ended up dead from hypothermia. In other villages, where the wheat was more easily distributed, there were celebrations. There were even a few weddings, the first in Abdulgan in four years.

The International Rescue Committee’s effort greatly slowed starvation deaths in Abdulgan, at least temporarily. If it were not for this action, it is nearly certain that few in Abdulgan would survive the winter. Now, several thousand, including Kashifi and Bakeh and Bakeh’s four daughters, probably will.

This may, however, be too little, too late. The International Rescue Committee would like to revive Abdulgan, but it seems an uphill battle. Too many people have died. People are still dying — in the first week of February, an undiagnosed disease struck the village of Zarda Badam, and 11 people died. As soon as the snow melts, it’s very likely that many of those who are healthy enough to leave will abandon their villages. Even the doctor wants to go. The Hazara have lived in these mountains for a thousand years, but this war may have been too much. It’s possible that by next winter the 55 villages of Abdulgan will cease to exist. They were never on the map to begin with, so there will be no need to cross them off.

— end —