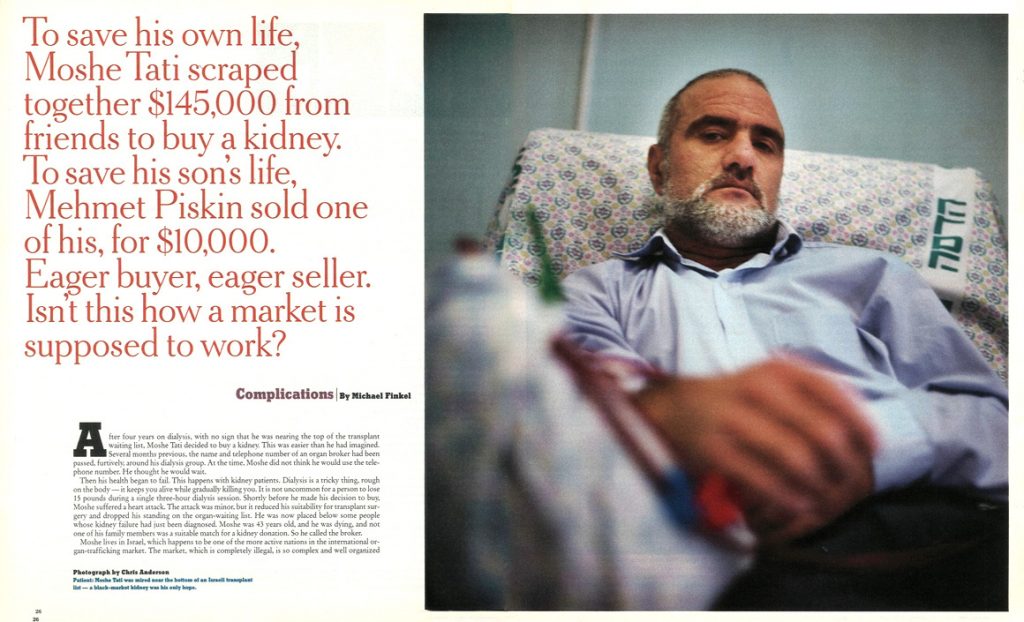

After four years on dialysis, with no sign that he was nearing the top of the transplant waiting list, Moshe Tati decided to buy a kidney. This was easier than he had imagined. Several months previous, the name and telephone number of an organ broker had been passed, furtively, around his dialysis group. At the time, Moshe did not think he would use the telephone number. He thought he would wait.

Then his health began to fail. This happens with kidney patients. Dialysis is a tricky thing, rough on the body — it keeps you alive while gradually killing you. It is not uncommon for a person to lose 15 pounds during a single three-hour dialysis session. Shortly before he made his decision to buy, Moshe suffered a heart attack. The attack was minor, but it reduced his suitability for transplant surgery and dropped his standing on the organ-waiting list. He was now placed below some people whose kidney failure had just been diagnosed. Moshe was 43 years old, and he was dying, and not one of his family members was a suitable match for a kidney donation. So he called the broker.

Moshe lives in Israel, which happens to be one of the more active nations in the international organ-trafficking market. The market, which is completely illegal, is so complex and well organized that a single transaction often crosses three continents: a broker from Los Angeles, say, matches an Italian with kidney failure to a seller in Jordan, for surgery in Istanbul. Though hearts and livers and lungs are occasionally sold, the business deals almost exclusively in kidneys. There are two reasons for this. First, kidneys are, by far, the organ in greatest demand — there are currently 48,963 patients on the United States kidney waiting list, and less than a tenth that number on the heart list. Second, the kidney is the only major organ that can be wholly harvested from a living person, leaving the donor essentially unharmed. (Recently, liver segments have also been transplanted from live donors.) In other words, with kidneys there are people who want to buy and people who want to sell — that is, a market.

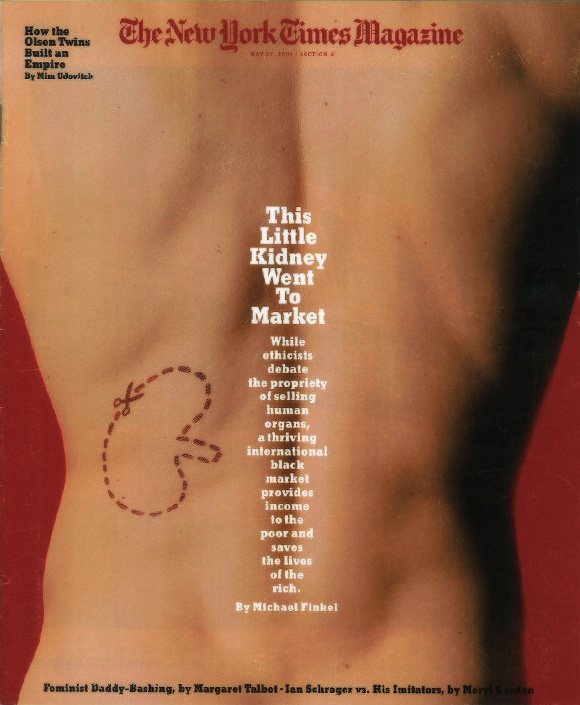

The sale of human organs, whether from a living person or a cadaver, is against the law in virtually every country (Iran is perhaps the only exception) and has been condemned by all of the world’s medical associations. In the United States, the National Organ Transplant Act, passed in 1984, calls for as much as a $50,000 fine and five years in prison if a person is convicted of buying or selling human organs. Francis Delmonico, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and the chairman of the ethics committee of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, says that paying for organs is ”morally and ethically irresponsible.” Bernard Cohen, the director of the Eurotransplant International Foundation, based in the Netherlands, calls the idea ”inhumane and unacceptable.” Pope John Paul II, in a recent address, said that the commercialization of organs violates ”the dignity of the human person.”

Yet in Israel and a handful of other nations, including India, Turkey, China, Russia and Iraq, organ sales are conducted with only a scant nod toward secrecy. In Israel, there is even tacit government acceptance of the practice — the national health-insurance program covers part, and sometimes all, of the cost of brokered transplants. Insurance companies are happy to pay, since the cost of kidney surgery, even in the relatively short run, is less than the cost of dialysis. According to the coordinator of kidney transplantation at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem, 60 of the 244 patients currently receiving post-transplant care purchased their new kidney from a stranger — just short of 25 percent of the patients at one of Israel’s largest medical centers participating in the organ business.

Relatively few transplant operations, illegal or legal, take place in Israel. Every proposed kidney transplant in the country between two unrelated people is carefully screened for evidence of impropriety by a national committee. Therefore, almost all of these illegal surgeries are performed elsewhere, in nations where the laws are easier to duck, including the United States. Israel also does not contribute much to the supply side of the equation. Organ donation is extremely low; an estimated 3 percent of Israelis have signed donor cards. Though several rabbis have declared that donation is permissible, there is a deeply ingrained belief in Judaism that the body must be buried intact so that it will be whole when it comes time for resurrection. Islam has a similar doctrine. (Christianity does not.) Neither Islam nor Judaism, however, has an edict against accepting transplanted organs. This situation makes the transplant waiting lists in Israel distressingly long.

Paying for an organ has become so routine in Israel that there have been instances in which a patient has elected not to accept the offer of a kidney donation from a well-matched relative. ”Why risk harm to a family member?” one patient told me. Instead, these patients have decided that purchasing a kidney from someone they’ve never met — in almost all cases someone who is impoverished and living in a foreign land — is a far more palatable option.

—

”I can get you a kidney immediately,” said the broker whom Moshe Tati called. ”All I need is the money.” Then he quoted a price: $145,000, cash, paid in advance. This would cover everything, the broker said — all hospital fees, the payment to the seller, accommodations for accompanying family members and a chartered, round-trip flight to the country where the surgery would take place. The trip would last about five days, he said, and the destination would be kept secret until the time they left.

The broker promised that one of the top transplant surgeons in Israel would be flying with them to perform the operation. The broker instructed Moshe to undergo blood and tissue exams so that a match with a kidney seller could be arranged. ”I can guarantee you a living donor,” the broker said, ”a young, strong man. This won’t be a cadaver organ.”

Desire for a living donor is another reason why dialysis patients often prefer to purchase a kidney and circumvent national programs, where legally transplanted organs are almost always from cadavers. An Israeli kidney buyer named Avriham, who used the same broker as Moshe Tati and traveled to Eastern Europe, described this notion in his own terms: ”Why should I wait years just to have a kidney from someone who was in a car accident, pinned in his car for hours, then in miserable condition in the I.C.U. for days, and only then, after all that trauma, have part of him put inside me? That organ is not going to be any good! Or, worse, I could get the organ of an elderly person, a person who died of a stroke or an aneurysm — that kidney is all used up! It’s better to take a kidney from a healthy young man who can also benefit from the money. Where I went, families were so poor they didn’t even have bread to eat. The money I gave was a gift equal to the gift I received. I insisted on seeing my donor. He was young and very healthy, very strong. It was perfect, just what I was hoping for. A dream kidney.”

Occasionally, cadaver kidneys are purchased on the black market, most notably in China, where the organs of executed prisoners are sold, but it is living sellers who are usually demanded. With good reason. ”A person who receives a living-donor kidney has a reasonable hope of a lifetime of kidney function,” says Richard Rohrer, the chief of transplant surgery at New England Medical Center in Boston. ”A person with a cadaveric kidney has a reasonable hope of a decade of kidney function.” The median survival length of a kidney transplanted from a cadaver is about 11 years; from a living donor, it’s more than 20 years.

There are rampant rumors, buzzing about the Internet, that to satisfy this desire for living donors, people are sometimes robbed of their kidneys. A victim is drugged, one story goes, and then wakes up, sans kidney, in a bathtub filled with ice. This crime has never been documented anywhere in the world, not even once. Other stories, also false, involve children being snatched off the streets in Brazil or South Africa or Guatemala by ”medical agents” in black vans. In truth, there is actually a global surplus of kidneys — sellers in India and Iraq literally line up at hospitals, often willing to part with a kidney for less than $1,000 — and therefore no need to steal any.

Moshe told his broker he’d get the money. At the time, he was working for the City of Jerusalem as a municipal sanitation inspector. He’d managed to keep his job while on dialysis. He told his coworkers about his desire to purchase a kidney, and a fund was established. More than 700 city employees donated, raising nearly $100,000. Moshe took out a bank loan to cover the rest. Then, a month after the original phone call, he informed his broker that the money was ready. The broker said they’d meet a week later at the Tel Aviv Hilton, and everything would be arranged.

At the Hilton, the broker told Moshe, ”We’ve found a perfect donor for you; he fits you like a brother.” Moshe was traveling with four companions — his wife, his wife’s sister, a friend from work and his friend’s wife. They handed over the money, a bank check for $145,000, and were driven to Ben-Gurion Airport, where a chartered plane was waiting. There were no papers to sign. ”Everything was done by handshake,” Moshe says. It was August 1997. On the flight there were three other kidney patients, one from Italy and two other Israelis, as well as an Israeli surgeon, two nurses, a psychologist, the broker and the patients’ traveling companions. It was only then, once he was aboard, that Moshe learned he’d be going to Turkey.

—

American dialysis patients have been significantly less eager than Israelis to enter the kidney market. Most Americans, it seems, harbor a deep-seated reluctance to engage in medical procedures done overseas. But the United States does often serve as a host country for the surgery. Foreign kidney patients occasionally arrive at U.S. hospitals with both a donor, also a foreigner, and a ready supply of cash. In the United States, there is no national transplant screening board; instead, every hospital has its own committee. Some facilities, especially those struggling financially, appear to employ a type of ”don’t ask, don’t tell” policy when it comes to transplant surgeries on foreigners. Brokers are familiar with these hospitals and sometimes fly in pairs of buyers and sellers, who sign documents attesting that no money is changing hands.

A few Americans do go abroad for paid transplants. A man named Jim Cohan, who lives in Los Angeles, helps organize such trips. Cohan insists that ”organ broker” is the wrong term for his profession. ”I call myself an international transplant coordinator,” he explains. He has been in the business a dozen years, he says, and has helped about 300 Americans.

”I got into transplant coordination when I discovered how long the waiting lists were and how many people were dying,” he says. According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, 2,583 Americans died last year waiting for a kidney. Worldwide, the number of annual deaths is estimated to be at least 50,000. ”There are plenty of spare organs to be had in other parts of the world,” Cohan says. ”There’s no need for a single person to die waiting for a kidney.”

No person of at least some means, that is. Cohan’s current price for a kidney, he says, is $125,000, all inclusive. ”First, send me $500, and I’ll send you an application,” Cohan says. ”You and your doctor fill it out. Once you’re accepted into the program, you have to send me a check for $10,000. The balance is due before you leave. Usually I can get an organ in less than a month. I send people to South America, to the Philippines, to China, Singapore and South Africa. Where you go depends on what’s going on in the world and what’s available.”

In a living-donor transaction, according to Cohan, only a small portion of the money actually goes to the person selling the organ — as little as $800 and rarely more than $10,000. The broker, he insists, takes a modest cut, around 10 percent. The majority of the cash is paid to the surgeons. It has to be big money, or they won’t be willing to risk their careers.

Cohan used to accompany some of his patients on trips. Then, in March 1999, he was arrested. He had been communicating with an Italian transplant surgeon who had expressed interest in working with him. It was a setup; when Cohan landed in Rome for a meeting, he was arrested by Italian authorities. He spent five months in prison. ”They claimed I was part of an international ring,” Cohan says, ”but it’s not true. I’m just in business for myself. So the courts let me go. There were no victims; there was no proof.” The Italian courts concluded that Cohan had not broken any laws.

Since then, he no longer travels. ”I do everything on the phone and on the Internet,” he says. ”I talk with doctors. I tell doctors about me, and doctors tell their kidney patients. I don’t buy organs; I don’t sell organs — I’m really just the producer. I produce operations. I just bring all the parties together. And I’ve never had any of my clients die.”

—

When Moshe’s plane landed in Istanbul, there was no need to clear customs, no one asking for passports. ”Everything was already taken care of,” Moshe says. ”The organization was like clockwork.” Moshe and the other three patients were driven to a hospital — An old hospital,” Moshe says, ”not modern, but very clean” — and their family and friends were taken to a hotel. Apparently, even the specific taxi that transported Moshe and his family was prearranged. ”The driver of the taxi that took me to the hospital had sold a kidney,” Moshe says. ”He showed me his scar. He told me he’d bought the cab with the money. He was very proud.”

The transplant surgeries were performed late at night, when the hospital was on skeleton staff and fewer people could question what was going on. An entire floor of the hospital, Moshe says, was requisitioned by the transplant teams. Two transplants were completed each night, the first starting at about midnight, the second at about 4 a.m. Two surgeries were done the night after they landed; two more the following night. Moshe was the last of the four to go. The surgery to remove the seller’s kidney, Moshe says, was performed by a Turkish team; the transplant surgery was completed by the Israeli physician and nurses who had flown with them.

”As I was being prepared for surgery,” Moshe says, ”I saw the man who was giving me his kidney. I just glimpsed him briefly. He was in an operating room across from me. We never spoke; when I saw him, he was already asleep, at the beginning of his surgery. I wasn’t nervous at all. I was about to start a new life.”

As Moshe awoke from his transplant surgery, the Israeli doctor was at his bedside, grinning. ”He told me, ‘Congratulations, everything’s great,’ ” Moshe says. ”He said I had already urinated. The first time in four years! He said it was a complete success. But I did not feel good. I felt pain from my neck to my stomach. Then I blacked out.”

Five hours later, when Moshe regained consciousness, the doctor was again at his bedside, with an entirely different expression on his face. ”I said, ‘Why are you looking at me like that?’ And then he told me.” Moshe had suffered a second heart attack, this time a major one. The other three patients were fine, but Moshe’s condition was grim. His entire body was swollen. Everyone was flown back to Israel, and Moshe was rushed to the hospital. Toxins were detected in his blood stream. Five days after receiving his new kidney, Moshe was operated on again, by a different surgeon, and the kidney was removed. ”The doctor told me the kidney was poisoned and dirty and black,” Moshe says. Most likely, this was the result of a vascular thrombosis, in which an artery or vein linking the kidney to Moshe’s body was inadvertently pinched shut. Moshe was in the hospital, recovering, for two and a half months. Never once was he contacted by the Israeli physician who performed the surgery in Turkey.

It has now been four years since Moshe’s transplant trip. The other three patients who traveled with him are healthy and free of dialysis. Last year they held a reunion, a festive transplant-day party. Moshe did not attend. He is on dialysis four times a week, three and a half hours a session. ”I feel tired all the time,” he says. Since the trip he has been unable to work, and he still owes money on the loan he took out to pay the broker. He is 47 years old. ”I thought about suing,” Moshe says. ”I wanted my money back. But there was no contract, nothing.” Even the discharge papers from the Turkish hospital were carefully prepared — they are on a plain sheet of paper with no address or telephone number. ”There is no way for me to prove where I’ve been and who performed the surgery,” he says.

Still, Moshe contacted a lawyer, who began the proceedings for a medical malpractice suit. Almost immediately, Moshe was contacted by the broker. The broker made him an offer: Drop the suit and whenever you want, we’ll take you abroad again, no charge. Next time, promised the broker, there will be no mistakes. Moshe accepted the deal. ”I’m still not ready to go,” he says, ”but dialysis is killing me.” Because of his heart attacks, he’s no longer eligible for the official Israeli waiting list. The broker’s offer is his only chance for a transplant. ”One day,” he says, ”when I’m prepared, I think I’ll want to try again.”

—

If you ask Michael Friedlaender to discuss Moshe’s case, he will tell you that the experience is a perfect example of why kidney sales should finally be legalized. Friedlaender is a nephrologist at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem; he treated Moshe both before and after his trip to Turkey. He is also one of the world’s most outspoken physicians on the issue of organ sales. In 1999, at a conference in Denmark, Friedlaender made the first public recommendation by an Israeli doctor that the laws governing organ sales ought to be changed.

”What’s happening now is absurd,” Friedlaender says. ”Airplanes are leaving every week. In the last few years, I’ve seen 300 of my patients go abroad and come back with new kidneys. Some are fine, some are not — it’s a free-for-all. Instead of turning our backs on this, instead of leaving our patients exposed to unscrupulous treatment by uncontrolled free enterprise, we as physicians must see how this can be legalized and regulated.”

A decade ago, Friedlaender says, he, like most physicians, was ”fairly violently opposed” to the notion of selling organs. Then, in the mid-90’s, his Arab dialysis patients suddenly began showing up in his clinic with new transplants. They’d been going to Iraq. Next, his Jewish patients began traveling, some to Turkey, some to former Soviet republics, and returning a week later with fresh kidneys. While there have been a few fatalities and a couple of disasters, like Moshe’s, Friedlaender discovered that the illegal transplants actually seemed better, in some ways, than the legal ones. When he compared his illegally transplanted patients with those transplanted in his own hospital, Friedlaender found that the percentage of illegal transplants still functioning after one year was, in fact, slightly higher than his own hospital’s success rate — and that of many U.S. hospitals. The difference, he says, is attributable to the benefits of transplanting kidneys from living donors.

”After I realized that,” Friedlaender says, ”I softened my stance. Examining those 300 patients brought me down from my high horse of ethics. Now I’m more practical. My patients don’t want my opinion on whether or not buying a kidney is moral — they want to know if it’s safe. And I have to say that it is. It’s as safe as having a transplant at a U.S. hospital. I realized that I had no right to actively stop my patients from going. I realized that it may be harming them not to go. So when they ask, I tell them, ‘Yes, you should go.’ ”

The current system of organ donation without remuneration, says Friedlaender, is a failure. Between 1990 and 1999, despite numerous marketing efforts trying to persuade people to sign donor cards, the U.S. organ waiting lists grew five times as fast as the number of organs donated. By the end of this decade, it is estimated that the average wait for a kidney will exceed 10 years. Even the more optimistic proponents of xenotransplantation — that is, transplanting from animals into humans, a procedure that could end organ scarcities — admit that such operations may be several decades away. It could be even longer before genetically manufactured organs are available.

As donated organs have remained difficult to procure, transplant operations have become safer and easier. The development in the early 1980’s of the powerful antirejection drug cyclosporin changed transplants from risky, experimental procedures into common, highly successful ones. ”We’re now at the point,” Friedlaender says, ”where it’s really not very complex to match organs. It’s no more elaborate than getting a blood transfusion. If sales were legalized, it would not be difficult to make sure people were buying clean, well-matched kidneys.”

Though Friedlaender is not directly involved with any of Israel’s so-called transplant tourism, he is familiar with a physician who has repeatedly been accused by the Israeli media, including one of the nation’s leading daily papers, Ha’aretz, of participating in hundreds of overseas transplants, many of them in Turkey. The surgeon’s name is Zaki Shapira. ”Shapira is a mastermind,” Friedlaender says. ”He’s made a big business out of this. I’m revolted by the amount of money he’s making, but not by what he’s doing. He’s helped a lot of patients. A lot of people owe their lives to him.”

Shapira, who is also the chief of transplantation at Beilinson Medical Center, one of Israel’s largest hospitals, refused to speak with me. However, a lawyer who is very familiar with his activities — a lawyer who insisted on anonymity — estimates that Shapira goes overseas with patients ”more than twice a month.” Shapira, she says, ”doesn’t feel as though he is bound by national laws if these laws do not suit him. He arrived at the conclusion that if he didn’t do something to stop people from dying on dialysis, then nobody would.” It’s unclear, she adds, which laws Shapira has broken, what the potential punishment might be and where he might be subject to jurisdiction.

Shapira’s activities have been investigated by the Israeli Ministry of Health, but he has never been charged with wrongdoing. ”Everybody knows what Dr. Shapira is doing, though we haven’t been able to prove it,” says Simon Glick, a Ministry of Health official who worked on the Shapira investigation. ”There’s not enough evidence. The patients won’t testify because he’s saved their lives. We had the police involved, but they threw up their hands at the whole thing. I think Dr. Shapira should be brought to trial, but I’ll bet he never will. Sometimes it seems to me that transplantation is as much a moral failure as it is a medical success.”

—

When asked to examine the issue from the other side — from the point of view of people selling their kidneys — Friedlaender admits that he worries about the exploitation of the world’s poor populations but that he doesn’t feel right telling people what they can or cannot do with their bodies. ”Medically,” he says, ”there is no evidence to show that donating a kidney endangers a person’s health in any significant way.”

Of the half-dozen studies performed on donors, including a 20-year follow-up, none have revealed any increased mortality. Health-insurance companies do not raise their rates for kidney donors. ”We allow people to give up a kidney for no payment at all,” Friedlaender says. ”Why won’t we allow it for pay?” After all, Friedlaender points out, everyone else in the transaction profits — the doctors, the hospital, the nurses and of course the recipient. ”Why,” he wonders, ”does the person losing the most have to do it for free?”

If kidney sales were legalized, he claims, brokers and rogue physicians would be out of business, and more money could flow to the sellers. Friedlaender’s ideas for a specific legalization plan mirror those proposed by other Israeli and American lawyers and medical ethicists. To start with, all organ sales would be arranged through a national regulatory body (in the United States, there would be several regional centers). A potential seller would register with the regulatory body and would be contacted when his or her kidney was needed. Criteria for the allotment of live-donor kidneys would be no different than the current system of cadaveric-organ distribution; that is, based on the length of time a patient has waited, the quality of the organ match and the direness of the patient’s need. The patient and the seller would never meet. The reduction in the number of dialysis patients would yield financial savings that the regulatory body would divide, allowing the seller to be well remunerated and, of equal importance, the recipient to not have to pay for either the organ or the surgery. Payment to the seller would be made either in cash — $25,000 has been discussed, paid through the regulatory body — or via an indirect method, like a reduced income tax rate or free health insurance. While sellers would almost certainly come from poorer populations, at least the recipients, under this plan, would include both the poor and the rich.

Depriving the sellers of an opportunity to profit, says Friedlaender, is an unjustifiable form of protectiveness: ”It implies that the sellers are ignorant and that they are endangering themselves. I believe it is paternalistic for us to judge the motivations and values of other people and other cultures.” It’s already legal, he notes, to sell semen and plasma and ova. And surrogate motherhood, also legal, carries far more risk, statistically, than kidney removal. In a recent paper titled ”The Case for Allowing Kidney Sales,” published in the British medical journal The Lancet, eight physicians from four nations write, ”If the rich are free to engage in dangerous sports for pleasure, or dangerous jobs for high pay, it is difficult to see why the poor who take the lesser risk of kidney selling for greater rewards — perhaps saving relatives’ lives, or extricating themselves from poverty and debt — should be thought so misguided as to need saving from themselves.”

—

”Paternalism,” says Nancy Scheper-Hughes, ”is the backbone of the medical profession. Medicine is all about care, and if you toss that out and reduce patients to a collection of free-market consumers, then doctors will lose whatever vestiges of moral authority they still have.” Scheper-Hughes is a professor of medical anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley, and a co-founder of a group called Organs Watch. Under the auspices of Organs Watch, Scheper-Hughes has spent three years traveling the world while investigating the organ market, focusing on human rights implications and violations of national laws. Her work in Israel was instrumental in exposing many of the nation’s improprieties.

As Michael Friedlaender’s views have gained acceptance — a survey in the United States by the National Kidney Foundation, cited in a recent issue of The Journal of Medical Ethics, showed that nearly half the respondents favored some form of compensation for organ donors — Scheper-Hughes has become increasingly alarmed. Kidney sellers, she says, are treated not as humans but as commodities. ”These people have been reduced to bags of spare parts,” she says. ”For doctors to justify this by saying, ‘Well, the seller is getting something out of it too,’ is unethical. Turning one person’s poverty into an opportunity for someone else is a violation of the most basic standards of human ethics. Doctors should not be involved in transactions that pit one social class against another — organ getters versus organ givers. Doctors should be protectors of the body, and perhaps we should look for better ways of helping the destitute than dismantling them.”

Scheper-Hughes remains unconvinced that selling a kidney is actually a low-risk activity. She says she feels that the chief tenet of the Hippocratic Oath — do no harm — is being violated. ”In these deals you are certainly harming someone else,” she says. ”You are harming the sellers.” The argument that the slight harm to the sellers is more than offset by the lifesaving potential on the other end of the transaction is also troubling to Scheper-Hughes. ”I call this ‘increasing the net good,’ ” she says. ”Is this really the kind of world we want to live in — one based on utilitarian ethics in which net gain to one relatively privileged population allows them to claim property rights over the bodies of the disadvantaged?”

Further, she points out, every study demonstrating that kidney donation does not compromise health has been conducted in a wealthy nation. ”It is not exactly clear that poor people can really live safely with one kidney,” she says. People who sell their kidneys, she adds, usually live in abject conditions and face greater-than-average threats to their health, including poor diets, low-quality drinking water and increased risk of infectious disease, all of which can easily compromise the remaining kidney.

The actual kidney-removal surgery may also not be as gentle as advertised. Even Michael Friedlaender admits that removal surgery is a more painful procedure than transplantation. After a surgeon has carved through skin, fat and several layers of muscle, getting at a kidney sometimes necessitates the partial extraction of the 12th rib. Short-term complications have been documented in nearly one in five kidney-donation surgeries. Rather than moving toward legalization, Scheper-Hughes says, perhaps what is needed is stronger enforcement of existing laws. She points out that almost no one, worldwide, has ever been convicted of organ trafficking.

There is further concern about the notion that sellers are making an autonomous choice. Lawrence Cohen, an associate professor of medical anthropology at Berkeley and the other founder of Organs Watch, has done much of his fieldwork in India. He recently studied 30 kidney sellers in the city of Chennai. Twenty-seven of them were women. Some of their husbands, Cohen learned, made it clear that if the men had to do heavy labor, it was only fair that the women contribute to the family income by selling a kidney. Cohen observed that in none of the cases did selling an organ significantly improve the family’s fortunes in the long run. ”If only I had three kidneys,” one of the women told Cohen, ”then I could sell two and things might be better.”

”Nobody seems concerned about the sellers,” Scheper-Hughes says. ”The buyers are supported by doctors, but no one represents the sellers. Nobody solicits their opinions. In this market, they have become an invisible population. Someone needs to listen to them. What do they have to say?”

—

At about the same time that Moshe Tati was busy raising money to pay his broker, a 44-year-old man named Mehmet Piskin entered a hospital in suburban Istanbul in order to have his blood and tissue tested so that he might sell his kidney. Mehmet had a steady job, collecting garbage for the Istanbul Department of Sanitation, but his salary was low. His health insurance did not adequately cover his family. He was living in a one-room apartment with his wife and three children, and his youngest child, Ahmet, was suffering from a degenerative bone disease. Ahmet’s knees and elbows were gradually calcifying; already, at age 4, his growth had nearly stopped. He had difficulty walking. A series of corrective surgeries could alleviate the problem, but they would cost Mehmet nearly $20,000, a sum he could never imagine saving.

It was Mehmet’s neighbor, in an apartment down the hall, who first suggested the sale. ”One day,” Mehmet recalls, ”my neighbor knocked on my door. He said to me, ‘Do you want to save your boy’s life?’ I said, ‘Of course I do.’ He told me that if I gave up a kidney I could save the boy.”

In recent months, Mehmet had noticed a distinct change in his neighbor’s fortunes. The neighbor had once been employed as a night watchman. Then, rather suddenly, he’d purchased a new car and opened his own business, selling men’s clothing. Mehmet asked his neighbor if he had sold a kidney. ”He told me he had,” Mehmet says. ”He told me he’d been in debt, and that selling his kidney had saved his life. He said the operation was safe. He said maybe I’d be slowed a little for a month, but then I’d be back to normal.” He also admitted to Mehmet that he was now earning money by finding other people willing to sell. ”I told him,” Mehmet says, ”that I needed time to think things over.”

Mehmet thought for three months. ”I realized I had no other alternatives,” he says. ”So I said O.K. I said yes. I never discussed anything with my wife. I just decided on my own.”

—

His neighbor took Mehmet to a private hospital on the Asian side of Istanbul. When they walked in, everybody seemed to know the neighbor. ”It was like we were celebrities,” Mehmet says. ”There were 100 other patients waiting, and we just went right in.” At the hospital, Mehmet met with a doctor and underwent blood and tissue tests. ”We talked about the price right there in the hospital,” Mehmet says. ”We bargained a little, but I was firm. I said I wanted $30,000, and I wasn’t going to take anything less. They agreed. I was told I’d be paid in the hospital, after the operation. There was no contract. Nothing was written down. It was a handshake. I trusted them — it was my neighbor, and it was a doctor. Of course I trusted them.”

Three days later, Mehmet’s neighbor knocked on his door. The surgery, the neighbor said, would take place tomorrow; he said they’d go to the hospital together. In the morning, Mehmet called into work sick. He was given a private hospital room. Elsewhere on the floor he saw the other sellers — all Turks, all poor people” — and the buyers — at least a dozen Israelis, on dialysis machines, waiting for kidneys.” (Wealthy Turkish kidney patients are also involved in the market; they tend to travel to India for surgery.) The nurses told Mehmet not to eat or drink.

Shortly before he was taken into surgery, he wrote a letter. ”It was a just-in-case letter,” he explains. ”In case something happened to me. I asked whoever found the letter to contact my wife. I put down her name and our address. I wrote, ‘Please give all the money to my wife, but do not tell her that I’ve given a kidney.’ I wrote, ‘Tell her that I’ve been in a traffic accident and have passed away, and that this is the blood money from the driver that hit me.’ I put the letter under my pillow.”

Then he was rolled into surgery. He caught only a glimpse of the person who was buying his kidney. They never exchanged a word. The doctor told him that the Israeli receiving his kidney was very sick and about to die. The doctor told him that he was saving a life. The last thing Mehmet remembers before his surgery is music. ”There was a stereo in the operating room,” he recalls. ”Foreign music was playing. Disco-dancing music. Loud. The doctors were dancing to it. One doctor was dancing with a scalpel in his hand. I had to laugh. A doctor asked me, ‘Why are you laughing?’ I said: ‘I’m happy. I’m happy because I will save my boy.’ ”

—

The surgery lasted a little less than three hours. ”When I woke up I had severe pain in my right side,” Mehmet recalls. ”I told the doctor about the pain and he gave me a shot. I felt better, and then I called my wife. I told her I’d been in an accident. I told her I was hit by a car while I was walking across the street.”

Mehmet’s wife, Sebnem, rushed to the hospital and stayed with her husband for two days while he recovered. ”I came into the hospital room,” Sebnem says, ”and I saw him lying there with so many machines and I thought, that can’t be a car accident. Mehmet insisted it was. Then I saw the envelope, and I knew something was happening.” The morning of Mehmet’s release, a doctor came into the room and handed Mehmet an envelope. Inside, in U.S. currency, in crisp hundreds, was $10,000.

”The doctor said to me, ‘When you come back to have your stitches removed, we’ll pay you the rest.’ I said, ‘Why not now?’ He said: ‘It’s a Saturday. The banks are closed.’ And so I left the hospital with the $10,000.”

On the cab ride home, Mehmet told his wife the truth. ”I’m still angry at him,” she says. ”One evening, a few weeks before the surgery, he told me that we’d be able to save the boy. I asked him how, and all he said was, ‘Don’t worry, we will.’ If he had told me what he was doing, I’d never have let him give a kidney. Never. He should have kept working. In the hospital, I heard the doctor tell Mehmet that when he came back he’d get the rest of the money. After Mehmet explained everything to me, I said to him right in the cab, ‘You left that money behind, and now you’ll never see it.’ ”

His wife was correct. When Mehmet returned to the hospital to have his stitches removed, the doctor was not there. His neighbor said not to worry. Mehmet phoned a dozen times, but the doctor did not return any of his calls. Meanwhile, the recovery time forced Mehmet to quit his job. He and his family left Istanbul and moved to the small farming village, about 100 miles away, where Mehmet had grown up. He had wanted to return home, and now he could. He spent most of the money fixing up a small house. He never spoke to the doctor again. The last time he telephoned his former neighbor, the neighbor told him that he’d pay Mehmet the rest of his money only if Mehmet’s younger brother, Mustafa, also agreed to donate a kidney. When his neighbor said that, Mehmet hung up the phone.

A few months later, a group of Turkish television journalists, working with the police, set up a sting operation and captured on film a Turkish surgeon named Yusuf Sonmez as he was about to begin what he thought was an illegal transplantation. Sonmez has been linked by Organs Watch with Zaki Shapira, the Israeli surgeon who has been implicated in the organs market. After Sonmez was filmed, he was arrested by the police and held for three days but was not charged with any crime — money had not yet changed hands, and there was no proof that it would. Punishment was left up to the Turkish medical association. Sonmez was banned from practicing medicine for six months. He has since been restored to full medical standing. Sonmez dismisses the whole thing as a setup.

Mehmet, meanwhile, has never regained his health. It has been four years since the operation. ”I’m not the same person,” he says. ”I swell up like a pregnant woman. I can’t sleep. I have not been able to work; my health has not allowed it. I go from place to place looking for work, and everyone says no. The economy is very bad, they tell me, and there are younger and healthier people to hire. The people of this village, they look down on me because of what I’ve done. I feel helpless.”

An American surgeon, after being told of Mehmet’s symptoms, suggested that Mehmet might suffer either from nerve-entrapment syndrome — in which a nerve was mistakenly caught in one of his internal sutures — or a type of hernia that can result if one of the layers of abdominal muscle the surgeon sliced through did not heal properly. Mehmet has not gone to see a doctor about his pain. He can’t. All of the money from the operation is gone. Mehmet’s wife is the family’s sole wage earner. Sebnem works six days a week in a refrigerator factory. She earns about $150 a month. The family can’t even afford electricity — instead, they have illicitly tapped into a power pole. Their son’s bone disease is still attacking and deforming his body. Ahmet’s wrists and knees are both nearly fused. He has a new growth on his chest. He rarely attends school.

”Everything is worse now than before,” Sebnem says. ”Mehmet was a healthy person, and now he is like this. Nothing is right. The wages have not been paid at the refrigerator factory in three months. Ahmet is crippled. We’ve basically been reduced to begging.”

—

The kidney market is an interesting business. It’s a business in which the satisfied customers keep quiet. Actually, not entirely quiet. Certainly they do not like to advertise what they have done — it is, after all, illegal — but they will talk with other kidney patients. This is how information is passed; by word of mouth, transplantee to dialysis patient. This is how Moshe Tati first learned about the broker. The business, like a back-room poker game, seems continually on the move. The place to go is always changing — first India, then China, then Russia, then Turkey. Lately, the kidney trade is said to be phasing out in Turkey and setting up shop in Moldova. Romania, too, seems to be an emerging player.

According to Friedlaender, though, one market trumps the rest. This market, he says, appears to offer kidney transplants performed by excellent surgeons, with careful screening of sellers, extraordinary postsurgical care and a success rate that evidently rivals even the finest U.S. hospitals. The program seems absent of false promises and persistent rip-offs. The price is a bargain. Some people have even idealized this program as a model of how a legalized system might one day function. It’s located in Iraq.

Michael Friedlaender credits the family of a young Palestinian named Sami (who spoke on condition that his family name not be used) for proving the effectiveness of the Iraqi system. Sami’s story begins on the afternoon of Jan. 30, 1999, when Sami, then a 22-year-old student at Golden West College in Southern California was involved in a car accident. When he was treated for his injuries, the doctor discovered that Sami had a severe kidney problem. It had nothing to do with the accident — it was, Sami was told, a genetic condition. He was immediately placed on dialysis and told that his siblings should be examined as soon as possible for signs of the same illness.

Sami had been living with his extended family in the United States and was in the process of applying for citizenship. He phoned home, to the West Bank, and his five sisters and two brothers were checked at Hadassah University Hospital. An older sister, Rana, and a younger sister, Samia, were also found to have chronic renal failure. Rana, who is now 27 years old, was the sicker of the two. She vividly recalls her first trip to Hadassah: ”I went into the dialysis center and I saw the machines and I started to cry. I wasn’t prepared. I saw people with tubes going into their neck and others with tubes going into their stomach. I saw the scars that the needles leave. I wanted to try something else; anything else.”

A kidney patient mentioned to Rana that if she wanted to avoid dialysis, the best place to go was Iraq. The family made a few phone calls. Rana’s father was given the name of a private hospital in Baghdad and told to simply show up. No broker was needed. While Rana still had limited function in her kidneys, she and her parents decided to travel.

Sami, meanwhile, was on dialysis three times a week in California, and on the U.S. transplant waiting list. He dropped out of college. ”I was told to be prepared for a three-year wait, minimum,” he says. He heard about his sister and the trip to Iraq and promptly left the United States and went home to the West Bank.

Rana was gone for 40 days. She returned in excellent condition, with a healthy, functioning kidney. The total price, for six weeks in a private hospital room, a furnished apartment for her parents, all medical fees and the payment to the seller was $20,000. She never had to endure a minute of dialysis. Her sister, Samia, went next, last February. She, too, was gone more than a month and returned with a perfect kidney. Samia, as well, never once had to be punctured by a dialysis needle.

Finally, last September, it was Sami’s turn. He and his parents took a taxi into Jordan. They spent a night in Amman then hired a car for the 10-hour trip to Baghdad. Sami was placed in a hospital room on a floor that was entirely reserved for illegal kidney transplants. On his floor he met people from Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Algeria, Libya and Morocco. His parents stayed in a nice apartment on the hospital grounds, with a full kitchen and maid service. When they arrived at the hospital they stopped at a special foreign-transplant office and paid the whole amount — $20,000, cash, U.S. currency. Sami’s father says that he was told that about $2,000 of this fee went to the seller. For a manual laborer in the Middle East, this represents as much as a decade’s salary in one shot.

—

On Sami’s second day in Iraq, he was introduced to his donor. The donor’s name was Essam. He was 24 years old, a Palestinian refugee residing in a Jordanian village. Essam was living with his parents and four brothers and one sister in a single room. The family had no money. Essam’s father was very sick and had gone blind. The Jordanian government does not provide welfare for Palestinian refugees. Essam, as the oldest son, felt that he had to help his family. So he took the bus to Baghdad. ”He was engaged to be married,” Sami says, ”and he said the money would aid his family and allow him to start his married life. He said he was happy to help me.”

Sami and Essam spent two weeks together, while both were carefully screened and prepared for surgery. ”The doctors are very cautious,” Sami says. ”If they doubt the donor’s medical condition even 1 percent, they don’t take him. The kidney has to be clean.” Essam was accepted as a seller, then had to sign a document attesting that he was a volunteer.

The sellers, Sami explains, live on a separate floor of the hospital. They are all men, all young. Most come from poor parts of Egypt or Jordan or Iraq. There is never a shortage of sellers. They arrive at the hospital and are tested, then they live at the hospital until a buyer with a good match appears. ”The sellers’ floor is like a dorm,” Sami says. ”Four guys to a room. The donors were always joking and playing cards. It was fun to go down there and hang out. I felt like Essam and I became brothers.”

Occasionally, Sami and Essam left the hospital and toured Baghdad. Sami’s parents took photos. There is a photo of Sami and Essam, arms around each other, at the Baghdad Zoo. Essam is a thin young man with a stubbly mustache and opaque eyes. There is another photo of them at a cafeteria. In a third picture they are dressed in light blue hospital gowns, emerging from an elevator just minutes before their surgeries.

Both operations went smoothly. Afterward, Sami spent 15 days in isolation, allowed no visitors. ”I had to talk on the phone with my parents,” he says. Paid transplantation is illegal in Iraq, but the government is either unaware that this is going on, or, more likely, the appropriate people are paid off. In any case, the patient care is exemplary. All other illegal transplant programs discharge their patients almost immediately after surgery, exposing them to infectious hazards and leaving the patients’ home countries to handle the resulting complications. Essam, too, according to Sami, was provided with ample recovery time. Then Essam returned to Jordan and Sami to the West Bank, where Michael Friedlaender is providing his after-care.

”After seeing the results,” Friedlaender says, ”I have to say if you’re going to do this, you should go to Iraq.” According to Sami, the hospital where he bought his kidney performs 100 illegal transplants a year, and there are at least six other hospitals in Baghdad with similar programs. ”They are all in communication with one another,” Sami says, ”to swap sellers, to find the best matches.” It’s not just for people from the Arab world, he insists. ”They are very nice there. Very welcoming. It’s a humanitarian thing.”

Sami and his two sisters are doing well. ”I’m feeling strong — strong and happy,” Sami says. He and Essam have kept in contact. They sometimes write letters. ”In my last letter,” Sami says, ”I invited him here for a visit, to come stay with me.” Essam, according to Sami, is fine. ”He used some of the money to support his family,” Sami says, ”and some to rent his own place.” Then, says Sami, he used the remainder of the money to pay for his wedding.

— end —